Haydn Sonatas

Haydn Sonata in B Minor Hob XVI.32 – First Movement Analysis

Haydn Sonata in B Minor Hob XVI 32

The First Movement of this Sonata follows, expectedly, the Allegro Sonata Form, that Haydn himself standardised. Within it, however, we encounter some unexpected elements, which might give us an insight in the process of developing this structure. Analysis of Haydn Piano Sonatas by WKMT. Haydn Sonata in B Minor Hob XVI 32.

In this Analysis, we will mostly follow the terminology and methodology of William Caplin.

GENERAL ANALYSIS of Haydn Sonata in B Minor Hob XVI 32

After listening to the piece and looking at the score, we can easily notice the landmarks that give away the expected structure of the Sonata Form.

EXPOSITION

- Theme A (of unconventional, but surprisingly tight-knit organisation) is clearly framed in bars 1-8, thanks to the clear Perfect Authentic Cadence (PAC) in the home key of B minor at bar 8.

Read on below, the DETAILED ANALYSIS, for the surprisingly controversial labelling of the Primary Theme.

The predicted Transition appears and modulates to the relative major key, ending with a Half Cadence (HC) at bar 12. It begins with an exact restatement of the basic idea (b.i.) in bars 9-10, a practice often used by many composers.

To see WHY Haydn chose to start the Transition with the original b.i., read the DETAILED ANALYSIS below.

So far, we can appreciate how obviously noticeable the end of each Phrase is, both to listen to but also to read in the score. Not only do they all symmetrically last 4-bars long, they also all end with some kind of cadence, which is also followed by a rest. Haydn is being unusually clear-cut, so far.

- Theme B (a Sentential-type, looser Theme) follows in the next 15 bars, in the subordinate key of D major. Its larger size is due to a series of extensions and expansions in all of its functions.

The Subordinate Theme is framed with the clear cadences and codettas in bars 22-28 and finally a rest (b. 28) after 11 bars of continual music.

The repeat sign in bar 28 verifies the end of the Exposition.

DEVELOPMENT

The Development’s structure appears to be in a “Rotational Form” (as described by Hepokoski and Darcy in their theory of Sonata Form), which is typical for Haydn. This means that the Themes and Motives of the Exposition, reappear in a similar order in the Development (and the Recapitulation, for that matter).

The Main Theme reappears (bars 29-37), varied and modulated in the Sub-Dominant and eventually minor Dominant regions (Em and F#m). The addition of a Sequence helps the modulation and contributes to the sense of destabilisation desired in this Section.

This ‘mild’ reimagining of Theme A functions as what Caplin would call a Pre-Core.

The new Theme A ends in a HC (and a quaver rest) in bar 37. The choice to avoid the PAC of the original Theme A is certainly a conscious one, since it’s a typical way of enhancing anticipation and imbalance at this point in the piece.

The new Theme B (bars 38-47) is where most of the Development’s ‘turbulence’ takes place. It combines motives from the Exposition’s Transition and Theme B, creating new material.

In bars 44-47 we encounter a Standing on the Dominant after a Dominant Arrival on the home key. This is a standard and expected technique of ending the Development.

Although this B unit includes this essential Framing Function (Standing on V), the lack of a large sequence within it, prevents us from characterising it a Core. Instead, we are going to call it a Pseudo-Core (as Caplin suggests).

RECAPITULATION

The Recapitulation Section (bars 48-70) kicks in with the characteristic b.i. in the Tonic key.

Theme A’s cadence is changed (again) for a HC in bar 53, postponing the Authentic Cadence even further.

The Transition is omitted in this Section all together.

Another interpretation would suggest that the Transition merged with the Main Theme. Since the Transition’s main functions would be the re-establishment of the home key and a HC leading to the Subordinate Theme, we can say that it does exist, hidden in the suspiciously sequential Continuation Phrase at the end of Theme A (bars 52-54).

Why is the Transition omitted in the Recapitulation?

As we will see later in the DETAILED ANALYSIS, apart from the main, functional purpose of every Transition (to modulate), this one fulfilled an additional need in the Exposition -that of restating the b.i. But the idea has been heard many times by the time of Recapitulation. Therefore, the composer has neither a need to transpose, nor to restate any idea. The transition has no purpose, so it is omitted.

Theme B (bars 55-70) is formally identical to the Exposition’s version, only this time it is stated in the B minor Tonic Key, as is usual for most Sonatas.

There are no additional Codas or Codettas in the Recapitulation. A reason might be that the PAC and original Codettas are a sufficiently strong closure to the piece, since there hasn’t been an Authentic Cadence since the beginning of the Development.

CLIMAX

What is a climax?

The climax should be defined as the highest moment. What characterises being at the highest, is the potential energy created, the need for resolution.

Therefore, the climax can be either literally the moment with the highest pitch (melody), or the most active and tense part in terms of harmony, rhythm and sound (texture, dynamics etc).

The climax in a Sonata Form is not as easily identifiable as it would be in a simpler form, consisting of one or two thematic units (i.e. a dance, or a song). Nevertheless, it should be proven useful to identify the climactic moments of the piece and of its sections.

Looking through the Exposition Section (bars 1-28) we can obviously point out many climactic instances, within each Phrase.

But since the Exposition is perceived as a complete and continuous musical unit, we should look for the highest of these climaxes.

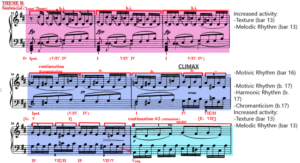

So what is the Climax of the Exposition?

The second Theme (bar 13 onwards) is clearly a more active one, in terms of texture (four voices) and melodic rhythm (semiquavers). A climactic ascension is initiated.

In bar 16, the Continuation intensifies the music further, with the addition of an accelerated motivic rhythm (fragmentation on the minim).

Finally, the middle of bar 17 reaches the highest point! It adds three more layers of activity, with a shorter fragmentation (crotchet), vast acceleration of harmonic rhythm (crotchet) and use of secondary dominants and chromaticism (resulting in loss of tonal centre).

The following bars have a decrease of activity elements (or an increase of resolutions), until the final resolution on the PAC.

Why is the Climax on bar 17?

Rather interestingly, but not surprisingly, the highest moment of the Exposition exactly corresponds with the golden ratio (φ).

The Section is 28 bars long. 28÷φ=17.3

The middle of bar 17, is therefore the best spot that Haydn could have chosen.

What about the Climax of the Development and Recapitulation?

Even though we could look at these two Sections individually, it is more appropriate to group them together. The lack of an Authentic Cadence until the end of the Recapitulation, strongly encourages this grouping.

We would expect to find the most distant keys, the most sequential harmonies, the tensest texture and most complex rhythms somewhere in the Development. But, the luck of a true Core (as explained earlier) keeps the music ‘grounded’.

Once again, the most climactic elements seem to be at the Continuation of Theme B in the Recapitulation (bar 59), equivalently to the climax of the Exposition (bar 17).

It contains all the same elements (four voice texture, acceleration of harmonic, melodic, motivic rhythm and this time with more chromaticisms) that lead us to label this a worthy Climax.

It would have been very impressive, had the composer arranged for it to appear at the golden ratio (which in this case would be bar 51). But an appearance on the three quarters of this double Section is close and good enough.

FOR THE PERFORMERS

As most composers of the time, Haydn trusts that the performer is musically trained enough that he need not be instructed by his Sonatas in the art of musical expression. This leads to very little dynamic and expression markings in most Keyboard pieces. In this case, no direct instructions are given by the Composer in the original text.

The score used in this analysis has added(?) dynamics to help the beginner (or even advanced) performer, but is by no means the only valid way of performing the music.

We will briefly discuss the two main sources of expressive decisions on a work like this. Those are the climax and the phrase function.

Climax Dynamics:

This is an obvious one. The general rule of thumb is that the dynamics should enhance the climactic moments of the piece.

In simple words climax=louder

What the performer needs to remember is that there are many climaxes in piece, each needing its own intensity and duration. The Exposition’s climax is of course more important than that of a Theme, Phrase or even motive.

Look above at the CLIMAX section to guide you on how to spot all the climactic moments of the work and enhance them.

Additionally, consider experimenting with the expectations by delaying or misplacing the dynamic climax or even contradicting and challenging the climax implied by the score.

Phrase Function Dynamics:

Reading through this Analysis, one will notice that not all Phrases have the same role and the Phrase itself is not an entirely homogeneous (and monotonous) musical unit. The dynamics should reflect these nuances.

For example, the first Theme (bars 1-8) consists of two Phrases.

The first Phrase (bars 1-4) introduces two distinctive ideas (b.1-2, 3-4). It would be reasonable to contrast between the two ideas dynamically. The first idea should be louder, similarly to how the first beat of a bar is usually louder (smaller scale) and the first movement of a Sonata is usually louder (larger scale).

That is why this version in particular uses mf and p for the first and second idea. Using f and p or other equivalents is also valid and common.

In fact, various contrasting expressive viewpoints have value (in this and other excerpts), as long as they are consciously chosen and musically supported.

DETAILED ANALYSIS of Haydn Sonata in B Minor Hob XVI 32

The purpose of this Detailed Analysis is to examine all the aspects of this piece as thoroughly as possible, with an insistence on Structure.

Hopefully, by the end of the analysis we will have a better understanding of this piece and of Sonata Form in general.

EXPOSITION

Theme A (bars 1-8)

GOALS: The purpose of the first Theme in the Allegro Sonata form (according to Caplin) is to:

1. Introduce and affirm the principal melodic-motivic ideas

2. Confirm the home key tonality

3. Define the degree of tight-knit organisation (explained below)

The first Theme of the Sonata Form is meant to be what Caplin calls tight-knit. In plainer words, it is ideally a typical, conventional, stable Theme.

But none of the conventional categories (i.e. Sentence, Period, Hybrids) fit perfectly here.

So what is this Theme? What makes it work even though it is Nonconventional.

For starters, let’s examine its functions.

The first two bars (or rather, first two metrical downbeats) are unquestionably the basic idea (b.i.). The position in the beginning and the tonic prolongation are enough to determine that it is indeed a b.i.

The b.i. can be divided in motive a (an ornamented arpeggio) and motive b (with its characteristic dotted quaver-semiquaver rhythm).

The following two bars (3-4, along with the anacrusis in bar 2) are a clear contrasting idea (c.i.). The new material used and -more importantly- the cadential progression ending it, clarify it is indeed a c.i.

However! The cadential progression mentioned (bar 4) is a Deceptive Cadence. This Cadence type is used as a tool to cause imbalance and insecurity, since it subverts our expectations of a Cadence and it demands a new resolution. Why does it appear here? Is this b.i.+c.i. meant to be an Antecedent, a Consequent, a Compound Basic Idea?

Analysing the following bars, will throw light on these questions.

After that deception (bar 4), an Extension is necessary, to achieve an Authentic Cadence.

In bar 5 instead of an Authentic Cadence (as expected) we receive a new single bar motive, repeated in bar 6 and bar 7. This ‘motivic acceleration’ is what we can label fragmentation.

The last fragmentation of bar 7 initiates a cadential progression that resolves in the tonic in bar 8, labelling it a Perfect Authentic Cadence (PAC). This is the best way to confirm the home key tonality (see GOAL 2 above).

Initially, we might be tempted to label the new motive of bar 5 an interpolation, because of the lack of connection with the previous material AND because it fails to give us the desired Authentic Cadence. However, retrospectively, we can see that it is part of a Continuation Phrase, which finally resolves and ends our Theme.

To summarise, even though the way by which Theme A is created is unconventional, it creates a surprisingly tight-knit, perfectly functional Theme. Haydn uses the extensions to end up in a conventional duration of 8 bars, while each subunit of it has a symmetric length of 4 or 2 bars. (GOAL 3)

The end result, even though labelled ‘Extended Consequent’, closely resembles a Hybrid (Antecedent+Continuation type), with the particularity of a Deceptive Cadence as the first, weak cadence (instead of a Half or Imperfect Cadence).

The basic idea and contrasting idea give a solid introduction to this Sonata’s motives. However, they fail to ‘affirm’ them, by not repeating them and not fixing them to the audience’s ears (GOAL 1). This will happen later.

Transition (bars 9-12)

GOALS: The purpose of a Transition is to:

1. Destabilise the home key and establish the subordinate key

2. Loosen the form

As mentioned in the General Analysis earlier, the Transition begins with the original b.i. in an exact restatement (bars 9-10).

Why does the transition start with the original b.i.?

The fact that today we know that a device is commonplace in Sonata Form, did not help the composer back then. Haydn had a real musical need for his choices. He needed to restate the b.i., because he chose an unconventional and hybrid-like type for Theme A, in which we only hear the main motive once (failing to fulfil Theme A’s GOAL 1). In order to compensate for that choice, he chose to restate and affirm the idea in delay, after the end of the Theme.

The c.i. of the opening (bars 3-4) is replaced with a new one (c.i.#2 in bars 11-12) that makes extended use of motive b of the b.i.

The Transition modulates to D major and ends on a HC with the use of pivot-chords (most importantly the IV of the new key in bar 11), establishing the new key (GOAL 1).

This transitional unit is surprisingly tight-knit, when we should expect a destabilised, loose structure (GOAL 2 failure) that would deem a stabler Theme B necessary. But Haydn uses other means to prepare us for moving on:

- This ‘over-use’ of motive b is both a motivic fragmentation suggestive of the upcoming cadence, and a motivic liquidation suggestive of a cleansing of the palette, so we are ready to receive the next Theme.

- Moreover, the c.i.#2 smoothly modulates to the Subordinate key of D major, making this a Modulatory Transition, pushing us forward.

- Finally, the interpretation of the unit keeps changing retrospectively. At first, one might perceive re-listening to the original b.i. as a Da Capo repetition. But quickly we move on to the new c.i. and the repetition ‘fails’.

We then might expect this b.i.+.c.i., ending with a HC to be an Antecedent opening a new Period. But it ‘fails’ at that too, since we move on to whole new Theme B after the cadence.

The originally perceived Antecedent, functions not as an opening up but as a closing down. To fulfil this functional purpose, it must be labelled a Consequent that (once again) ‘fails’ to meet an Authentic Cadence.

To summarise, in the few second that the Transition lasts, there is a constant re-interpretation of structure in the listeners mind after constant ‘failures’, a clear modulation that contributes in the imbalance and a motivic liquidation that saturates the music and adds to the need of moving on.

Theme B

GOALS: The purpose of the second Theme in the Allegro Sonata form is to:

1. Contrast the first Theme melodically and rhythmically

2. Confirm the subordinate tonality

3. Loosen up the formal organisation.

Right of the back are shocked with the striking chord on the lower register followed by the thicker contrapuntal texture, and the rapid semiquavers that create the single bar b.i. (bar 13).

We already have started fulfilling all the goals of the second Theme. The melodic-rhythmic contrast of the two Themes is striking (GOAL 1).

To continue developing the loosening of organisation, Haydn repeats the irregularly short b.i., not once, but twice (bars 14-15), creating an unusual 3 bar Presentation Phrase.

The entirety of the Phrase is, of course, supported by prolongation on the new tonic of the Subordinate Key, by means of a Pedal Point (which is performed on the lower voice and doubled on the ‘alto’ voice).

The following three bars (16-18) are a Continuation which utilises two of the four typical compositional devices. There is fragmentation on the minim (b. 16-17) and then on the crotchet (b.17-18) and acceleration of the Harmonic Rhythm (b.17-18). It does not include sequential harmonies and an acceleration of the surface rhythm.

At the end of this Continuation, we do not find a Cadence (as we would expect), but the beginning of an extension, a new Continuation (bars 19-21), that further loosens the organisation.

The listener does perceive this as new material (rather than an expansion of the same continuation), because of the sudden change of range of the lower registers (G# resolving down to A) and the subtle change of texture (omission of a voice).

The main difference in the second Continuation (b.19-21) is the use of a model-sequence progression harmonically and melodically, which was absent in the first, but the prominent component of the second.

The sequence is moving from V (b.19) to I (b.20) and then to IV (b.21) where it breaks the pattern melodically and harmonically.

This sequential extension of the Continuation function aids in achieving the goals of Sonata’s Theme B, by loosening the formal organisation even further (GOAL 3).

In bars 22-23 we receive the anticipated Cadence in the form of a Perfect Authentic Cadence (PAC). The Cadence is then repeated identically (b.23-24) using the ‘one-more-time technique’.

Finally, a Codetta with cadential character is stated (b.25-26) and restated (b.26-28).

This Cadence is extended from 2 bars to a total of 7 bars (22-28). This finally fulfils the aim of loosening even more the formal organisation (GOAL 3) and confirming the subordinate tonality with a series of cadential progressions (GOAL 2).

Another thing worth mentioning here is that the triplets of semiquaver, which are prominent in bars 22-25, appear out of nowhere. That is a little trick, we could say, that Haydn plays, to que in the cadence. Abruptly changing the saturated thematic material and texture (‘over’-used in bars 13-21) for short, scalic, motivically insignificant, texturally thin notes (b.22-25), he signifies the ‘beginning of the end’ or ‘wrapping-up’. This is a stereotypical, yet effective way to approach the Cadence. The composer masterfully utilises this trick. (liquidation?)

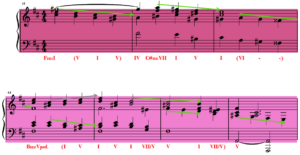

DEVELOPMENT

The Development is the freest and most creative section of the Allegro Sonata. Within the frame of a binary structure (Pre-Core and Core) the Composer can Develop his elements as much as he dares.

As mentioned earlier in the GENERAL ANALYSIS, Haydn organises the Development Section with Pre-Core and Pseudo-Core.

One would benefit by comparing the Exposition and Development (even bar by bar) since it follows the framework of a “Rotational Form” (meaning that the motivic material re-appears in the same order as in the Exposition).

The beginning of the Development (the entire Pre-Core of bars 29-37) is almost identical to the Main Theme. This sense of ‘rebeginning’ is a typical feature of the Classical era. Only restrained creativity and variation is shown so far.

The most important features of this Pre-Core are:

- Motive a of the basic idea is used as a modulatory introduction (bars 29-30)

- The real basic idea is stated in the Subdominant Key of Em (bars 30-31)

- The Deceptive Cadence of the Exposition (b. 4) is replaced by a more abrupt Evaded Cadence (b. 34)

- The Continuation of Theme A is now transformed into a modulatory model-sequence towards the Minor Dominant key of F#m (b. 34-37)

- There is only weak HC ending the Pre-Core (b. 37)

WHY did Haydn choose these five features?

All these elements give the impression of familiarity and change at the same time. They provide the desired feeling of exploration, gradually getting us out of our comfort zone and keeping us at the edge of our seat.

In the final ten bars of the Development (b. 38-47) Haydn creatively combines material of the Transition and Theme B to create the response to the Pre-core; the (Pseudo-)Core.

The b.i. and c.i.#2 reappears almost exactly, forming a Presentation phrase (b. 38-40).

The Continuation phrase (bars 41-47) is the essence of this new Secondary Theme. It is the Core of the Core, if you will. It uses only one motive of the c.i.#2 (the dotted semiquaver-demisemiquaver) and the Texture of the original Theme B

The most important features of this Pseudo-Core are:

- Tonal Exploration (starting on Fm, moving to A, C#m and Bm)

- Retransition to the home key (bar 44)

- Standing on the Dominant (after dominant arrival) in bars 44-47

The elements not used:

- Model-Sequence

- Half Cadence

It is because of the lack of a large Model-Sequence that we characterise this unit as a Pseudo-Core.

A reduction of the Continuation phrase is shown below.

The reduction enlights us on two interesting factors. Range and Melody.

The Range of this 8-bar phrase starts up in the high and dense registers (C#5-G#5) in bar 41 and finishes in the low/middle and wide registers (F#1-C#4).

The Melody is made of constant down-step movements. In any moment, one of the voices will be moving downwards, with occasional doubling in the 3rd or octave. The sole exception is in bar 44, where the downwards movement in the left hand voices is contrasted with an upward movement on the right.

This permanent feeling of moving down contrapuntally, but also the overall move to lower registers, is the melodic compensation of the lack of a strong harmonic cadential progression to finalise the Development.

Recapitulation on Haydn Sonata in B Minor Hob XVI 32

The Recapitulation is the rounding-up section of the Sonata Form.

The essential GOALS are:

- The restatement of the Exposition’s thematic material

- The necessary adjustments to avoid modulation

- A strong affirmation of the Home Key through the final Cadences and Codettas

All the goals are easily accomplished here, by simply restating the Exposition, almost identically.

Read again the GENERAL ANALYSIS of Haydn Sonata in B Minor Hob XVI 32 above, where we explore the masterful way by which Haydn handles the second goal of adjusting the modulation.

Do not miss our Haydn Sonata in C HOB XVI 35 Analysis.