Haydn Sonatas, Music Theory Resoucers

Haydn Sonata in C Hob XVI 35 Analysis

Haydn Sonata in C Hob XVI 35 Analysis

or

How to Be Unique But Not Irrelevant

In this Analysis, we will mostly follow the terminology and methodology of William Caplin. You can read the previous analyses to get familiar with the terms that will be used here. Haydn Sonata in C Hob XVI 35 Analysis.

Introduction – Why Analyse Another Sonata?

The reader is assumed to have some knowledge of music theory and be at least vaguely familiar with the overall structure of a Sonata Form. This analysis could be an affirmation of theoretical knowledge or an encounter with the principles in the real world.

This is useful by itself, but it is not all.

By analysing in detail this Sonata, one should be able to understand more than just the language and idioms of Haydn or 19th-century Classical music. We must try to comprehend the forces and tendencies (or Muses, in the ancient language) that guided the composer. Today, one needs not compose like a German of the Classical period to be aligned with the spirit of Haydn. This alignment is the ultimate goal of this analysis.

Haydn shows us a way to be innovative, yet traditional. On one hand, he is in many ways defining the Sonata and the entire language of the Classical period. On the other hand, he -like most brilliant minds since ancient times- considers himself to be a discoverer rather than an inventor. Almost as if the Sonata Form pre-exists him and he is merely trying to discover it, to uncover the mysteries of the universe, to hear the Music of the Spheres, as the Pythagoreans would say.

Musica Universalis or Music of The Spheres represented as Heavenly Principalities.

The unexpected twists on the Form are used as a tool to search for a “truer” Sonata Form. Similarly, on a higher level, the creation of the Sonata in general (mostly by Haydn) has been an attempt to discover and understand higher forms of musical complexion and Principles, by expanding the Ternary Forms of the earlier tradition.

Taking this Sonata as an example, we can find an answer to the problem of Post-Modernism, whose language has dominated art in the last 100 years. Instead of Deconstruction and Disenchantment, Haydn’s goals are to Reconstruct and Build Up the Sonata structure. Like expanding an old church, renovating and rejuvenating it, as opposed to creating a building that would challenge the concept of church building.

Therefore, Haydn doesn’t confuse novelty with quality. Yet he understands the value of Challenging Norms as a means to discovering the patterns above, NOT as a goal to themselves.

His participation in a broader identity, without losing his own unique language (Union in Multiplicity) is a refreshing antidote to the idiosyncrasy and particularity of Postmodernism.

In the In-Depth Analysis section, we will attempt to look into the motivations of the composer, but first we must get familiar with the music in the Overall Analysis. Haydn Sonata in C Hob XVI 35 Analysis.

OVERALL ANALYSIS

Knowing the structure of the Sonata Form, we should be easily able to identify the expected Sections and elements. Nevertheless, Haydn still has in store some surprises for us. Haydn Sonata in C Hob XVI 35 Analysis.

The EXPOSITION begins with an 8-bar PRIMARY THEME in the form of a tight-knit Hybrid (Compound Basic Idea + Continuation).

The following 8 bars are an almost exact repetition of the initial 8 bars. The obvious difference is the triplet quavers on the left hand, which increase activity and propel us forward.

So, is this actually a 16-bar Compound Period? Is the initiating Theme an introduction to the more active second appearance of the Theme? Or is the second part a sort of extension? Which part of the Theme is more “real”?

These questions shall be answered in the In-Depth Analysis section later.

As soon as the last cadence resolves in bar 16, a 5-bar Closing Section begins, by means of elision (bars 16-20). This Closing Section affirms the Home Key, utilising tonic prolongation. It also frames the Primary Theme, which will help us answer the questions stated in the previous paragraph.

Notice that, while prolonging the tonic key of C major, the composer controversially included the B♭ note (bars 16&18), hinting at the F key. How does he affirm the tonic by hinting at a different tonality? How can this counter-intuitive move work? We will answer in the In-Depth Analysis below.

Expectedly, we encounter the TRANSITION (bars 20-35) which elides with the end of the Closing Section before (bars 16-20). It contains all the elements we would from a proper Transition. The material used is new but based on the ideas of the Primary Theme. The structure resembles the “continuation phrase”, consisting of 1-bar fragments (b.20-26) and then minim-long fragments (b.27-32). It modulates to the dominant key of G major (b.23) and ends on a half cadence (b.32). It even includes a post-cadential Standing on the Dominant (b.32-35). All the elements of a clear Transition are here.

The only unexpected element is the long duration. While most Transitions last 4-8 bars, this one confidently reaches 16 whole bars.

The next Section is the SECONDARY THEME (bars 36-67). Here Haydn is unexpectedly dividing the theme into two independent parts, creating Secondary Theme A and B.

Luckily, William Caplin has already analysed these Secondary Themes himself, so we can draw the analysis straight from his book.

The First Secondary Theme (b. 36-45) is a 10-bar-long Cadential phrase, supported by a cadential harmony of I (prolonged for 6 bars)- II – V – I.

The Second Secondary Theme (b. 46-67) is itself divided into smaller parts.

The first part of Secondary Theme B is a Continuation Phrase (b.46-50). Much like the Secondary Theme A, this Theme also lacks an initiating phrase (like a Presentation or Antecedent) and is instead launched with a sequential and fragmented single-bar cell.

After the PAC (bar 50), the Continuation Phrase is immediately restated (b. 51-62), this time expanded (doubling the duration of each fragment to two bars) and slightly varied. It is a similar thematic variation to that of the Primary Theme, which was also repeated with shortened value notes, but not expanded.

After an extension of the cadence, through the evaded cadence in bar 60, we arrive at the PAC in bar 62, which launches the expected final Closing Section (b.62-67) of the Secondary Themes which essentially frames the entire Exposition.

Even after knowing the labels and the technical elements of this section, we must still ask ourselves:

Why is the First Secondary Theme cadential?

Why is the Second Secondary Theme repeated?

Why are there two Themes?

These irregularities will be addressed later.

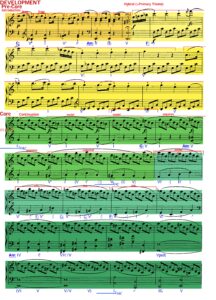

Moving towards the DEVELOPMENT section, we encounter what Caplin calls the Pre-Core/Core Technique of organisation. Moreover, the Development follows another pattern of the Classical Era in which the Pre-Core resembles the Primary Theme (“re-beginning”), while the Core draws elements from the Secondary.

We are “eased in” the PRE-CORE (bars 68-79) by an introductory phrase (bars 68-71) which draws heavily from the Primary Theme’s continuation phrase (bars 5-8), which is adjusted to modulate and end on a Half Cadence in A minor.

Modulating to the relative minor key of our home key (C major) is a conventional practice for the Development’s tonal organisation.

However, in an unexpected, near-comical way, we abruptly modulate in the subdominant key of F major.

Thus the main part of the Pre-Core begins (bars 72-79), which is essentially an exact restatement of the original 8 bars of the Primary Theme, only changing the key.

The Pre-Core ends with a PAC, which elides with the beginning of the CORE (79-103).

The Core features most of the essential features:

- Model-Sequence (bars 80-83 & 86-89)

- Tonal Exploration (mostly F and Am, but also going through E, G and C)

- Retransition to the home key (bar 101)

- Half Cadence (bar 103)

It does not include a proper Standing on the Dominant, although bars 44-46 do resemble one.

Technically speaking, the first element, the Model-Sequence is included. However, we must note that it does not appear in the “typical” way that was established eventually. In this Sonata we hear two bar-long models (bars 80 & 86), whereas the “proper” way would be to have a larger model (4-8 bars long). Still, the element is present and impactful.

Finally, motivically speaking, the Core is a combination of the two Secondary Themes.

The motives from the Secondary Theme A are:

- the anacrusis

- the V-I harmony

- the 5-1 melodic leap on the left hand (on the right hand originally)

The motives from the Secondary Theme A are:

- the anacrusis

- the sequential move a second upwards (downwards originally)

- the triplets on the right hand

Analysing the RECAPITULATION (bars 104-end) will be most productive if we compare it with the Exposition.

The section begins clearly with a re-introduction of the Primary Theme in the home key (bars 104-111). It is, as expected, almost identical to the Exposition, with the only difference being in a lower register. WHY did Haydn even choose to move an octave lower? We will explore this in the In-Depth Analysis.

In bar 111, Haydn already starts to diverge. He unexpectedly resolves the Perfect Authentic Cadence on the parallel C minor. (Possibly valid labels would be Evaded or even Deceptive Cadence, but we leave that open for interpretation by the listener).

This unexpected resolution initiates the Recapitulation’s Transition (b. 111-125) which includes elements from both the Main Theme and the original Transition (bars 20-35). This Transition starts with what we can call a pseudo-sequence (b. 111-117) to explore neighbouring tonalities, only to finish as the original Transition (b. 118-125), using fragmentation and a Standing on the Dominant of our home key.

The restatement of the Secondary Theme 1 (b. 125-134) is essentially identical to the original, changing of course the key to C major.

The restatement of the Secondary Theme 2 (bars 125-160) is identical to the original until the expected cadence (bar 151) is jarringly interrupted by replacing the V with a VII/V, thus labelling it “Abandoned”. The following extension (b. 152-160) is an interpolation of, yet again, the Primary Theme, but we are technically still expecting the final resolution of the Secondary Themes. The Pedal Point on the V enhances the anticipation of the resolution which eventually comes with the Authentic Cadence (b. 160).

CODA (bars 161-170)

To be precise, this is technically an extension of the Secondary Theme’s Closing Section (b. 62-67), by means of repeating the original Codetta. However, taking into account the entirety of the Sonata History, this is a Proto-Coda.

Either way, the force needed to stop and frame the entire piece is obviously larger than that needed originally to end the Exposition alone. Haydn strengthens the last Closing Section/Coda in the same consistent way that he has been reinforcing the rest of the elements; by means of repetition.

IN-DEPTH ANALYSIS – How the exception can serve the rule.

In this section, we will look in more detail at the exceptional points that got our attention during the General Analysis above.

By focusing on the exceptions, we should be able to understand the overarching principle of each of the Sonata Sections, that applies in this work as well as in the more conventional works.

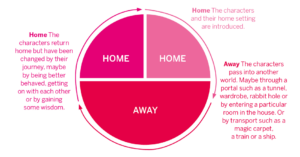

Before continuing, the reader must understand that the goal of this and any Sonata is not to merely follow the rules for the rules’ sake. The goal, the telos of the Sonata Form is to tell a story. A story about two different Themes, two contrasting Characters, that leave their Home and react to one another in unexpected ways, only to return Home, back to their expected ways. But they don’t return exactly the same.

This Principle is more important than any rule of composition. The rules are allowed to be broken if by breaking them the artist serves the higher Principle of the story.

This is a traditional pattern of storytelling seen in the graph below:

Credit: https://www.teachwire.net/news/use-circular-stories-to-help-children-understand-structure/

Also, one should keep in mind that there is no such thing as a “perfect” Sonata. The Form is a way of being, and if one attempts to compose everything by the book, the result would not be “perfect”, but “generic” and “soulless”.

So let’s see what Joseph Haydn did instead.

How to Frame the Primary Theme:

As mentioned earlier, the Allegro begins unconventionally. More than just framing and labelling the opening correctly, we must understand what the composer is accomplishing with it.

To answer this we should try to get into Haydn’s shoes.

The Sonata Form came as a sort of expanded version of the Ternary Form. There is the Small Ternary (approximately 24 bars long), the Compound or Trio Ternary (48-62 bars long) and then came the need for a larger form that would follow the fractal pattern of the ternary (A-B-A, or I-V-I, or Home-Away-Home). So the Sonata Form was developed (100+ bars) and naturally, it carried along the habits and tendencies of the smaller Ternaries.

The tendency that was inherited in this case is the exact repetition of the initial Theme. In Small Ternaries, the first 8 bars are usually repeated in the form of double bars on the score. In the Compound Ternaries, the first 8-bar Theme is usually written out again and restated with minor variations (and then all repeated with double bars).

When Haydn wrote this Sonata, he naturally followed that tendency of repetition. Even though the sensibilities changed with time and along came other, more subtle ways of establishing the core elements of the Movement, we must not anachronistically judge Haydn. For his time, the exact repetition was a standard method of initiating a work and it still remains structurally solid.

So what does he accomplish? By doubling down on his Main Theme, he re-enforces the sense of Home, the sense of familiarity and safety on his Theme, the reassurance that this is our Protagonist.

This doubling down on home, naturally creates the necessity for a doubling down on our Antagonist. Haydn does succeed in this too later, during the Secondary Theme.

But how is the Primary Theme framed and labelled then?

It is valid to label it in two different ways.

Firstly, in its essence, it is a regular 8-bar Theme which has been doubled of the old ternaries.

The proof of this is that Haydn only restates the original 8 bars during the Recapitulation (bars 104-110), while replacing the unessential doubling of bars 9-16 (and the Closing Section of bars 16-20 and the first phrase of the Transition of bars 20-26) with an almost Sequential, new Transitional phrase (bars 111-117).

In fact, every time it reappears, it is treated like a regular 8-bar Theme. We see it in the Development (bars 72-79) and for a second time in the Recapitulation (bars 153-160)

Moreover, both the Theme and the repetition end with a PAC, giving them autonomy to one another (in contrast to the Compound Period, in which the two Compound Sentences rely on one another for their existence).

Secondly, in its function, it is a Compound Period of 20 bars.

The proof of this is the Closing Section (bars 16-20) which frames and binds the entire Theme together.

Moreover and more importantly, the entire rest of the piece treats these large proportions as real and is adjusted accordingly.

In other words, the “heart” of the Primary Theme is a regular 8-bar Theme, but its “body” is a 20-bar Theme. One should notice that to recognise the Theme when the composer brings it back, the “heart” is sufficient (b. 72, 104, 153).

Why is the Second Theme so Irregular?

The short answer is that to rival an irregular opponent, you must become irregular yourself.

As we mentioned earlier there are three irregularities with the Secondary Theme which we need to address: a. It is divided into two parts, b. both parts lack an initiating function, and c. the second part is both extended and expanded.

Perhaps, asking “why” is a difficult question. For now, a more fruitful question would be “What is achieved by these irregularities?”

There are two Goals that need to be covered in the Secondary Theme section:

- To introduce a challenging rival to the Primary Theme/Protagonist

- To differentiate the nature of the two Themes/Characters

Because of the irregularities of the Primary Theme (mentioned earlier), the Secondary Theme accomplishes its Goals by adapting and utilising its own irregularities.

- In response to the Primary Themes repetition, extension and general enlargement to 20 bars, the composer rivals it by bringing two opponents, two Secondary Themes, instead of one (Goal 1).

- By omitting the initiating function on both of these Secondary Themes, their nature is contrasted to that of the Primary. They become, as Caplin puts it, “formally dissonant”. They become the loose opposition (“chaos”) to the tight rule of the Primary (“order”). The Dominant to its Tonic. (Goal 2)

- The extension and expansion of the Secondary Theme B, manages to mysteriously achieve both of the Goals at the same time.

On one hand doubling down on the Theme, in a similar way that the Primary Theme is doubled, does strengthen it in our memory, making it challenging to the sovereignty of the latter (Goal 1).

At the same time, the elements that are repeated are elements which only loosen the structure. The Secondary Theme B is made entirely of fragments and sequential harmony. By repeating them and even expanding them, the structure is loosened and weakened even further, contrasting it to the tight-knit Primar Theme (Goal 2).

We can therefore appreciate the genius of the composer. His formal decisions are not merely an aesthetic particularity that reflect the moment of composition. Rather, they have an important structural purpose.

Why Does the Recapitulation Start an Octave Lower?

or Set-up and Pay-off

or out of the Sea Monster

When we enter the Recapitulation, we encounter the Primary Theme (bars 104-111) in the original form. As mentioned above, the Theme is seemingly unnecessarily moved an octave lower and then the register is essentially restored right after (bars 111 onwards).

Was this change necessary? Was it merely an aesthetic decision? Is there any functional purpose to it? Is there a meaningful purpose to it?

One of the reasons is related to what is happening on bars 111 and onwards. The Transition is intentionally initiated abruptly. Apart from the harmonic surprise (the resolution on the Parallel Minor) and the new material, the moving of the register is also surprising. We are therefore tricked into believing that we are in a new high place, when in fact we are right where Haydn wants us to be, at the normal register.

It is indeed possible that Haydn worked this process out backwards, as we did to analyse it. It could also be an intuitive decision. It is not important. What matters is that it is definitely not unintentional, since it is not just a quirky way to restart the Primary Theme, but a set-up which pays off. There is a functional purpose even in this detail.

Apart from the functional, there is probably a purpose related to the meaning of the Sonata.

As mentioned earlier, the Sonata Form often resembles the traditional story-telling structure. One related story structure is the Hero’s Journey, in which the Protagonist faces the challenge of dark opposing forces and comes out of them victorious and renewed. There is an infinite amount of stories following this pattern, two of the oldest and most famous would be Jonah eaten by the sea-monster and Odysseus travelling to the underworld.

Looking at the end of the Development section we notice that we are already in low registers. One could naively suggest that the composer ‘did not have a choice’ and had to start an octave lower.

But obviously, Haydn is in control of his composition. Notice how the second part of the Core (bars 86-103) is heavily based on the Secondary Theme B (bars 46-62). It is, however, in many ways an inverted and gradually more ominous re-interpretation of our Antagonist. The stepwise sequence is now driving us lower and lower into the abyss.

It is in that place, at his lowest, that we re-encounter our protagonist. And he (surprisingly) jumps out of that place renewed (bar 111).

Must every Sonata embrace this “Katabasis” aspect of the Hero’s Journey? No, but it helps and it obviously works.

Is it certain that the composer was even conscious of these decisions? Definitely, not. It is certain and evident that he did make these decisions, and he did enrich his work with this ancient pattern.

That B♭ Note

While prolonging the C major tonic in the Closing Section of the Primary Theme (bars 16-20) the B note is sometimes flat (b.16, 18) and sometimes natural (b.17, 19), leaving us in an uncertainty between the C and F tonalities. Yet, it works. Why?

Since this is a rare phenomenon, we cannot simply find a by-the-book definition, but we have to make educated guesses to explain the situation.

There seem to be two reasons for this game of tonalities:

- To weaken it in relation to the second Closing Section (bars 63-67).

Since there is usually no Closing Section after the Primary Theme, but only after the Secondary, a strong Codetta here would have created the impression that the entire exposition has finished. Instead, the composer weakens this Closing Section, only to have the latter one sound stronger in comparison.

Notice that the B flat-natural alternation (instead of a simple B flat) is intentional. It keeps the harmony from becoming too Dominant, leading us to assume that this is the Standing on the Dominant of the Transition (which actually takes place in bars 32-35).

- Not to hint the G tonality yet.

The composer is obviously aware that the Transition is where the modulation to the Dominant tonality usually takes place. To clarify the grouping of the Sections, he puts the opposite force here, at the end of the Primary Theme, so he hints at the opposite direction of the Subdominant. Otherwise, the lines would have been blurrier and one might have thought that the Transition had already happened.

He therefore plays with the expectations of the audience who have been trained to expect the Dominant Key to arrive and he responds with a playful “wait for it”.

Conclusion on Haydn Sonata in C Hob XVI 35 Analysis

The elements of this work have been studied and are proof of how being musically innovative doesn’t mean being rebellious, but it can serve a higher purpose. Haydn certainly manages to look beyond the “rules” of the textbooks and aligns himself with the ancient and eternal forces of narrative and music. Hopefully, he can help us aim in that direction too.