Uncategorized

Why should we learn Counterpoint?

The technical aspect of Western Classical music has its origin in Counterpoint.

From this, Harmony emerged from one parameter, the vertical aspect, which established a more significant aspect in music, the form, which started to be considered one of the main aspects during the Classical period (1740-1810 approximately) and behaved as a structuring factor.

Counterpoint focuses on simultaneously linear or horizontal and harmonic or vertical parameters. In other words, it controls the melody (pitch and surface rhythm), and by layering different melodies, a vertical aspect emerges, which also is controlled and delineated by this technique. This concept was later called “Voice Leading“, and in Harmony, it is a by-product of the Contrapuntal technique.

By incorporating the concept of voice leading to the criteria used by the five species in Counterpoint will allow us to define the two planes on which the musical discourse is based: expression and structure.

The “what” is the structure on which the “how” is manifested.

Musical coherence is found in the “what“, while expression is found in the “how“.

(Eduardo Checchi. Counterpoint and Polyphony, P. 652)

By the study of the five species in Counterpoint, we will acquire a profound level of control which will allow us to grasp what are the relevant structural notes of a piece through analysis and afterwards, to be able to compose having a total mastering of these two crucial aspects in the music.

Firstly, we will concentrate on knowing how the system with its maximum expression with the great composer Johann Sebastian Bach came into being.

It is pretty common to disregard the study of Tonal Counterpoint that this technique was finally refined thanks to hundreds of years of constant development. Then we will plunge into studying the five species and how to incorporate their concepts into our compositions and/or analysis.

To clarify this, we will see two examples that explain the difference between the structure and its expression.

We will see in the following examples taken from the book “Counterpoint in Composition – A study of voice leading” by Felix Salzer, that the “what” unfolds very differently in the “how”

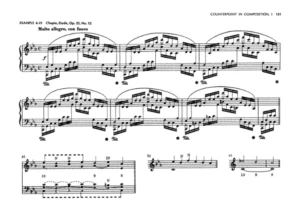

Etude Op. 25 No.12 (F. Chopin)

“Counterpoint in Composition – A study of voice leading” by Felix Salzer – Page 131

What appears first is the actual manuscript (the “how”); below it (left side) appears only the structure (a) which takes more and more elements through (b) and finally (c). What remains is a reductionism of the piece, just the pure “what”.

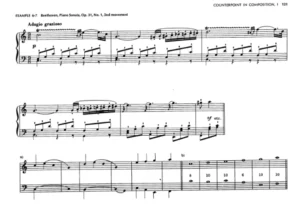

Piano Sonata Op. 31, Ni. 1. 2nd Movement (L.V. Beethoven)

Similarly, this example shows the clear directional motion that appears below the score. The music has been bereft of all expression.

Historical Context in Our Study

“Today, it is unlikely to achieve an exact musical result from a specific historical period, apart from being a completely useless undertaking.

A composition in a purist style only allows a result that is at least contrived. The world on which a language is created belongs to it. Wanting to include ourselves from the outside, with expressions typical of a bygone era, allows us to obtain a false copy that lacks all property and authenticity.

This last statement means that we must know, from our worldview, the elements that have created different expressions and syntax. Because this knowledge allows creating work methodologies applied to musical discourse, the exercises that illustrate the conceptual contents here are not intended to resemble the periods where these procedures reigned, but rather exemplify them “from the outside”, paying respect to the principles on which they are based.

We take advantage of the context by working on it rather than recreating them.

The most important thing is the elaboration of certain concepts that can assist the creation, just as on more than one occasion we see in works that apply these concepts adapting them, without being similar to the expressions that have been used in the past.

Even incorporating all the aspects that a certain period uses, with a deep understanding of those elements, means that we want to include them as outsiders of the initial syntaxis that this music was created.

Although the constituent elements of a given syntax may be felt, there remains the doubt whether this feeling of understanding is merely our way of grasping a process that may differ from that particular epoch lived. The experience is not transferable.”

(Eduardo Checchi. Counterpoint and Polyphony, P. 655)

In summary, all of our studies will focus on understanding from our paradigm, with our mindset, but paying respect and trying to recreate the intention and purpose that the composers conveyed centuries ago with the acceptance of our paradigms from which we catapult a clear understanding of the evolution music has accumulated, thus creating today’s complexity and richness.

The Focus of Our Study

The German ethnomusicologist Walter Wiora proposed in his work The Four Ages of Music (1967) and marked a division that will bring us closer to the vision of History that we will try to trace in this course:

1. First Age

The Age of Memory. Musical cultures prior to the development of musical notation. (before 1100 AD)

2. Second Age

The Age of Notation. European musical culture is based on the development of musical notation. (After 1100 AD until 1930)

3. Third Age

The Age of Sound. Global musical cultures, based on the development of sound technologies (creation, diffusion, commercialization) (1930 to the present)

We will undertake our study with the musical traditions that have been preserved to this day and sustained and developed mainly thanks to the use of musical notation.

A particular case will be the medieval Monody (Gregorian chant and troubadours) since they are musical corpus that, although formed and developed in a medium still unknown to musical notation, could be preserved later through notation.

Music As A Culture

The consideration of music as a culture – that is, as one more element of the fabric of cultural and social codes that shape how we relate to our environment- constitutes a revolutionary change of perspective produced in the field of ethnomusicology during the 20th century.

From the point of view of this study, music is a “sound” inserted in society through a set of “behaviours” and “ideas”.

Up to the 60′, ethnomusicology focused its study on the “raw materials” of music: scales, modes or rhythms.

Alan P. Merriam stated that this “raw material” constitutes only one aspect of music. For Merriam, music is a phenomenon that cannot be described solely by sound. It also requires the study of the behaviours that accompany it and the ideas generated around music.

Music generally takes place in a social act (behaviours) whose actors act according to certain norms.

On the other hand, music is not an ideologically neutral phenomenon but is usually inserted into a system of values and conceptions.

All these considerations concerning the interweaving of music in culture will help us realize that music is not an autonomous entity whose evolution responds only to its own rules or art mandates. On the contrary, however, this evolution constitutes a component and a reflection of the transformations in society, which ultimately determines its meaning and validity.