Music Theory Resoucers, Uncategorized

Historical Framing of the XV Century: Guidelines to Understand Renaissance Music

Historical Framing of the XV Century: Guidelines to Understand Renaissance Music

Before we plunge ourselves into the study of the music of the Renaissance period, we should take a brief look at the historical context in which this music thrived.

The historical framework that places the 15th century as the end of the Middle Ages and the beginning of the Renaissance period contains certain milestones such as the decline of the medieval scholastic mentality and its replacement by a new humanist paradigm, the invention of the printing press by Johannes Gutenberg (ca.1450), the fall of the Byzantine Empire (1453) and the discovery of America by Christopher Columbus (1492).

Within the arts, the Renaissance is considered an Italian phenomenon, developed by the patrons of the Quattrocento and exported to the rest of Europe throughout the 16th century.

Upon this vision, the Renaissance is understood as the rediscovery of classical Greco-Latin culture – a new paradigm supported by a concept of beauty and balance centered around the human being and his senses.

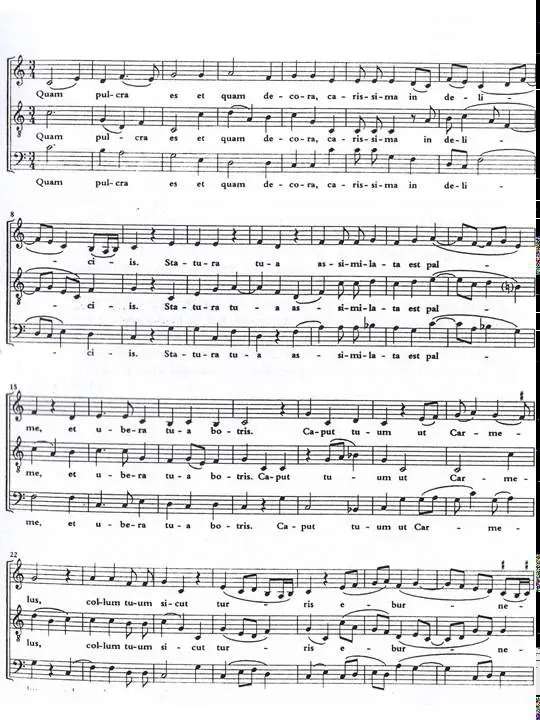

On the other hand, the abandonment of medieval polyphony – against the Ars Nova reacted with manifest contempt – developing softer and more melodious sounds (suavitas). The new style (already codified in 1477 by the theorist Johannes Tinctoris) welcomes the “imperfect” consonances (thirds and sixths), whose origin is located in the “Contenance Angloise” practised in the British Isles and imported to the continent by John Dunstable at the beginning of the 15th century.

“The ,Contenance Angloise,, or English manner, is a distinctive style of polyphony developed in fifteenth-century England which uses full, rich harmonies based on the third and sixth. It was highly influential in the fashionable Burgundian court of Philip the Good, and on European music of the era.” (Wikipedia).

Example of Contenace Angliose: John Dunstable “Quam Pulchra Es”

The Polyphonic Discourse of the Renaissance Period

Since the beginning of the Polyphony with the organum, the central concept of the polyphonic technique was to superimpose or overlap different melodic lines, each offering its distinctive personality; This was the core of the Ars Antiqua.

The polyphonic texture differentiates of the cacophonic one as it employs specific criteria that organizes this “overlapping” of the voices. The latter means that Polyphony considers what occurs simultaneously in all the voices, being the marriage between the horizontal and the vertical plane.

The main differences between the musical expressions between the Medieval period and the one in the XV century are the rhythmic counterpoint (mensural notation) and the simultaneous attacks of the various voices through perfect consonances within a piece.

According to Eduardo Checchi on his book “Counterpoint and Polyphony” (page 602), the XV century elaborates its discourse from:

- The concordance of simultaneous attacks with perfect and imperfect consonances, inherited from the English sonority (Contenance Angloise, see above)

- The fluid melodic discourse from Italian influence

- Overlapping of phrases of different length

- The “perpetual variation” criteria (resource of the Franco-Flemish school) or paraphrase. (paraphrasis). The paraphrasis as a resource of musical variation is a broad notion if we compare it with the modern notions of development (antecedent-consequent-model-sequence, augmentation, diminution, insertion, and expansion). The paraphrasis was used in a much abstract sense.

These characteristics aforementioned mean that for the first time, we have a Pan-European musical discourse.

As a final note, the paraphrasis refers to possibilities of temporary expansion of melodic element. At the same time, the concept of variation that started to be used from the 17th century allows changing the directional content without altering its meaning.

Both notions refer to horizontal discourse, that is, to the melodic one.

Example of Flemish school Josquin Desprez: Missa Pange lingua – Kyrie

Below we find the Gregorian chant on which the composer based his “motive” (or proto-motive as we may call it for now) he kept the first semitones between E-F-E to establish the “finalis” in this case, Phrygian mode:.

Try to see the motivic connections between them:

Guillaume Dufay – Missa L’Homme Armé for 4 voices, written ca. 1460.

00:00 – 0. L’Homme Armé {anonymous}

00:46 – I. Kyrie

05:43 – II. Gloria in excelsis Deo

14:38 – III. Credo in unum Deum

27:27 – IV. Sanctus

37:36 – V. Agnus Dei

Above we can appreciate two of the main pieces that offer what the Renaissance music developed in all its glory. Observe the nature of the melody of each voice and try to see how this “paraphrasis” unfolds through the numbers two Masses. Try to find “motivic connections” among them.

WKMT LESSON – 12.NOV.2020 – VIDEO LINK : Historical Framing of the XV Century: Guidelines to Understand Renaissance Music

*Do not miss my previous post, analyzing the tonal materials.