Music Theory Resoucers, Piano Lessons, Uncategorized

Complete Analysis – Clair de Lune by Debussy

It is known that Claude Debussy started writing this romantic piano piece, Clair de Lune, in 1890, when he was on his 28, but it wasn’t published until 15 years later. The wait was indeed worth it. Let’s go through Clair de Lune by Debussy.

GENERAL MUSIC ANALYSIS of Clair de Lune by Debussy.

FORMAL ANALYSIS:

This article is meant to fully analyze the famous piece: Clair de Lune by Debussy.

The terminology used in this analysis of Clair de Lune by Debussy, mostly derives from William Caplin‘s ‘Analysing Classical Form: An Approach for the Classroom’.

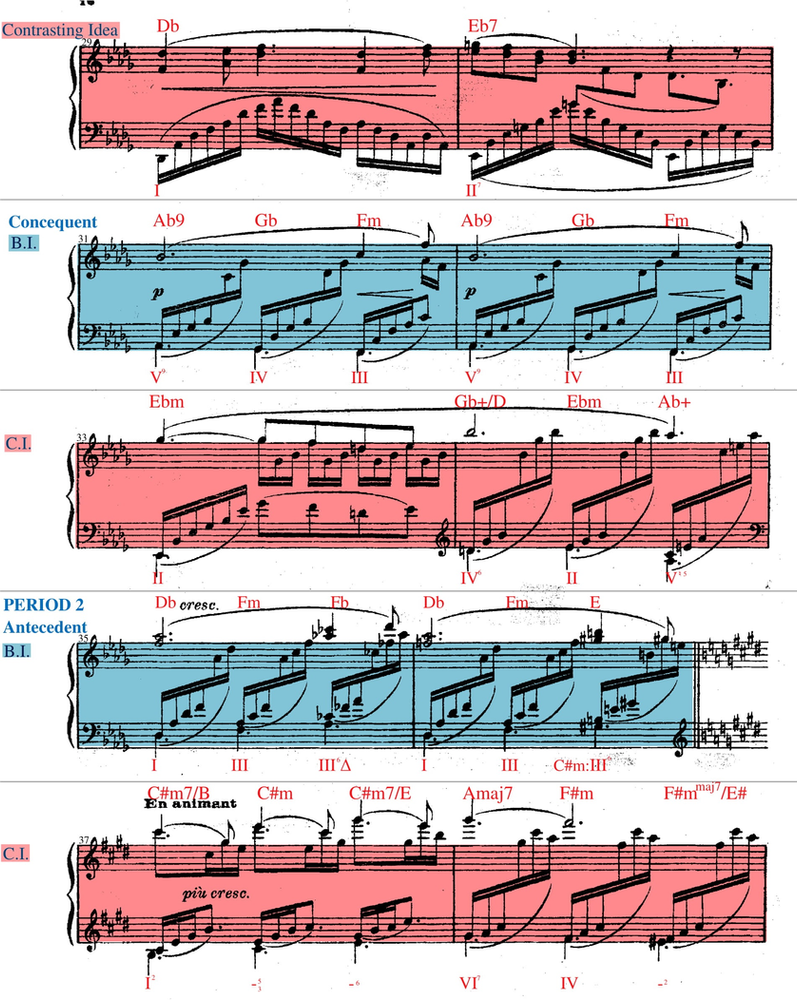

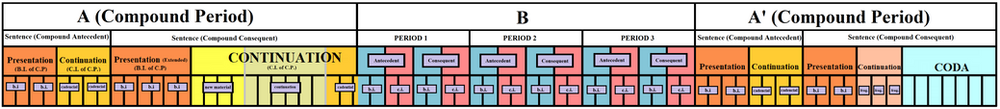

The piece has an ABA’ Ternary Form of 72 bars (26, 24, 22, respectively)

Section A is an extended Compound Period (bars1-27),

Section B is a series of 3 regular Periods (bars 27-50) and

Section A’ is a variation of the original Compound Period with an additional Coda in the end (bars 51-72)

Notice that the end of A elydes with the beginning of B.

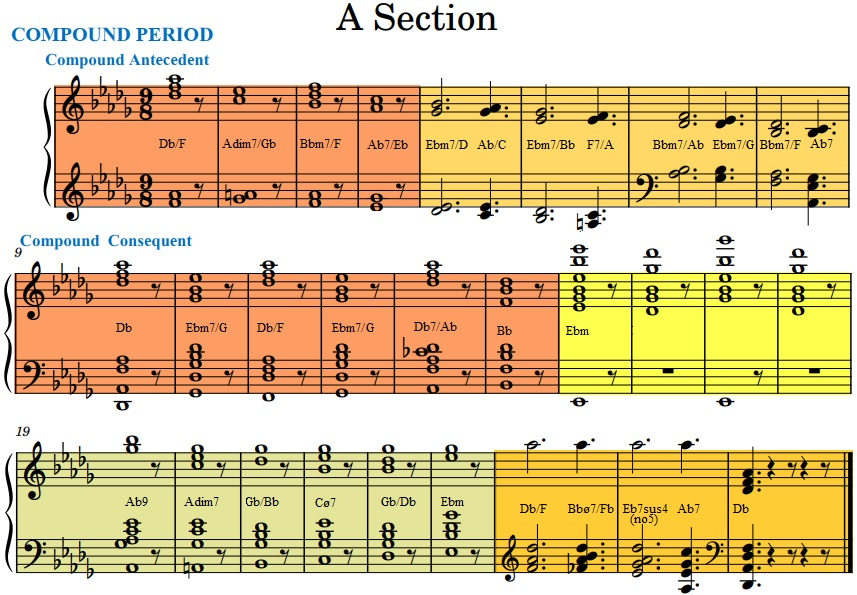

The Compound Period of A consists itself of a Compound Antecedent and a Compound Consequent (bars 1-8 and 9-27), which both take the form of a Sentence (made of Presentation+Continuation).

Let’s now analyze each of the sections.

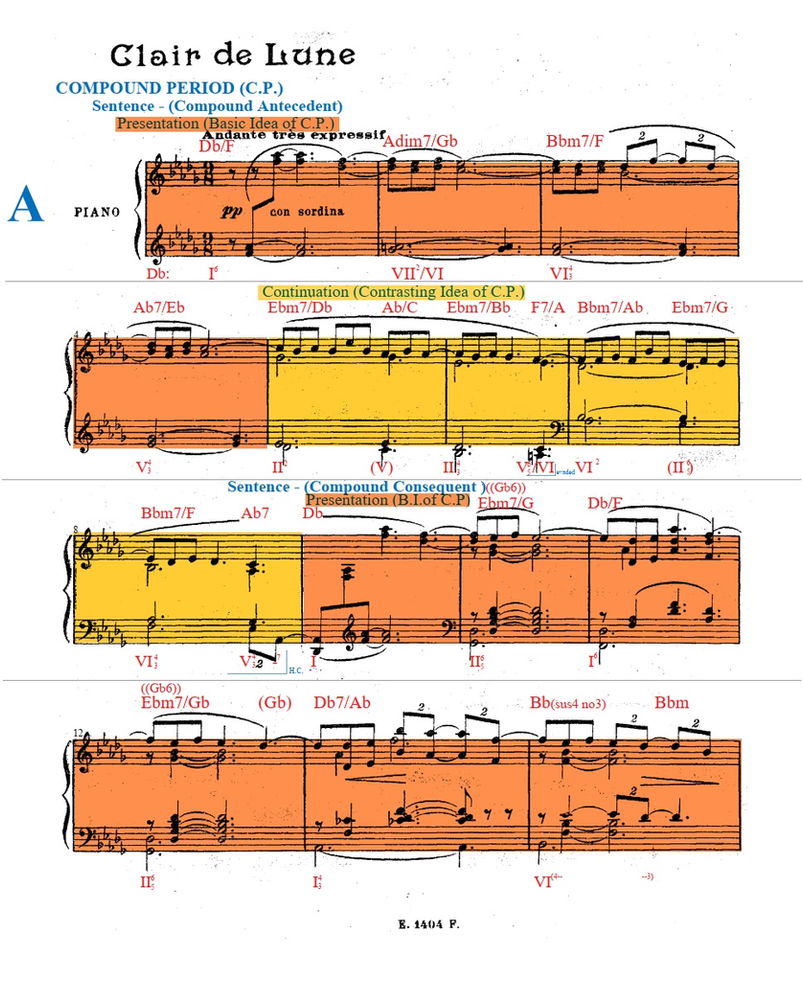

A SECTION

1. Compound Antecedent (Sentence)

The First Section initiates with a 4-bar Presentation (Basic Idea+Basic Idea), which functions as the big Basic Idea (bars 1-4) for the big Compound Period.

This big Basic Idea is contrasted with a 4-bar Continuation, functioning as the big Contrasting Idea (bars 5-8). This Continuation is actually made of two 2-bar Cadential Functions. The first does not resolve as expected but ends with an F7 chord (V/VI) in bar 6, resembling the Evaded Cadence of the Common Practice.

The whole 2-bar cadence is restarted using the ‘One More Time Technique’ (bars 7-8). This time we reach a proper Half Cadence ending the Compound Antecedent in bar 8.

2. Compound Consequent (Sentence):

The Compound Consequent starts with the return of the big Basic Idea (bars 9-14), which has been extended to 6 bars taking the form of an Extended Presentation (Basic Idea+Basic Idea+Basic Idea). We will see later in the Motivic Analysis how Debussy handles these repetitions.

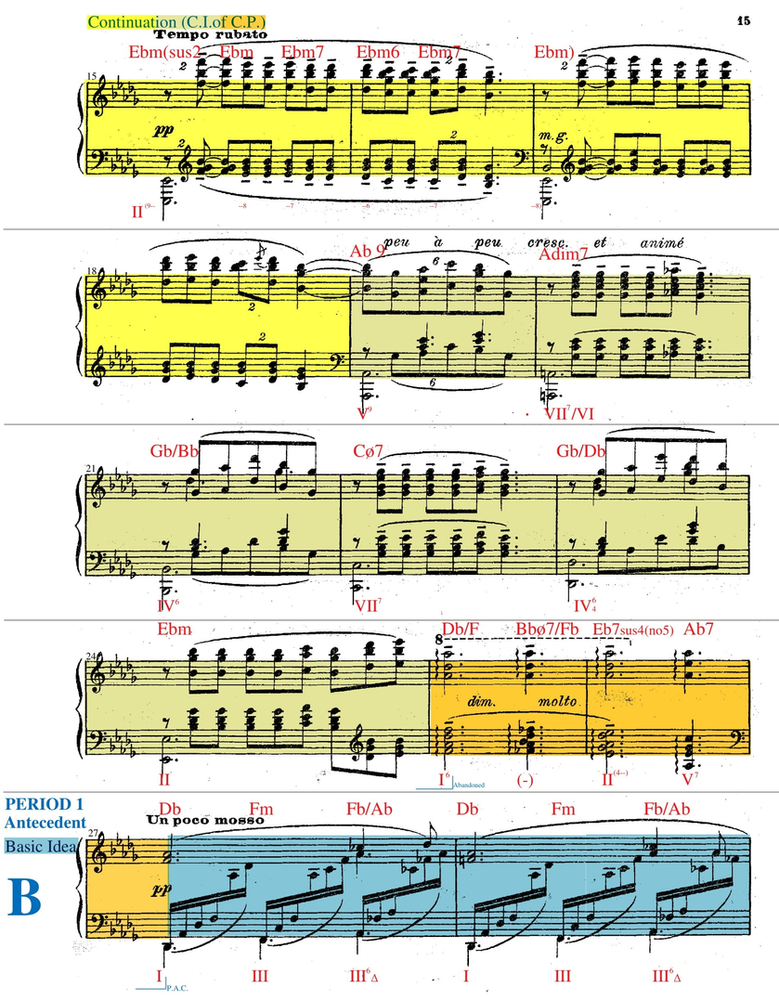

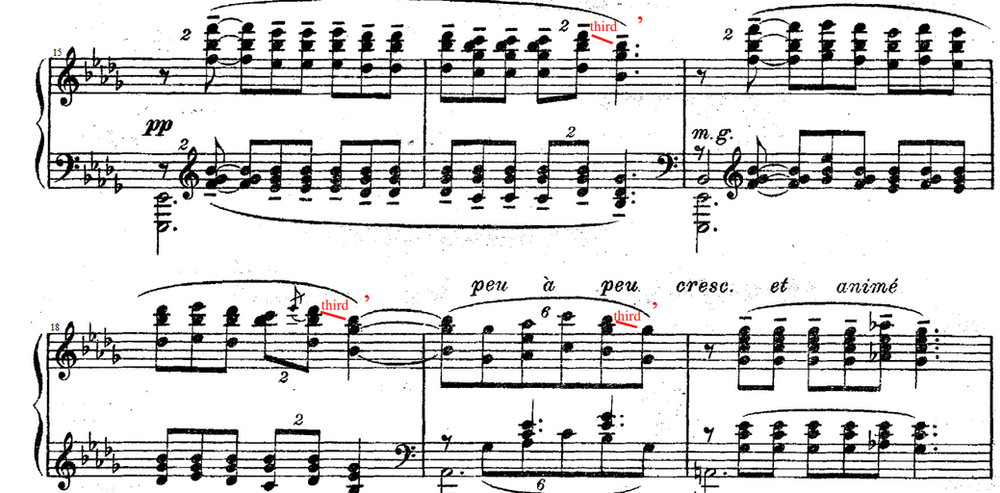

After that, we have a huge Continuation (bars 15-27) functioning as the second Contrasting Idea of the Compound Period.

This Expanded Continuation is almost as big as the three Phrases preceding it, and we can divide it into three Parts itself.

In the first Part (Yellow in the score, bars 15-18) we don’t have clear elements of a Continuation or Cadential Function, however, we do have motivic elements that have been watered down, liquidated, that connect us to what we heard before. One could understandably call this Part an Interpolation since it does not add much to the form, but we could also view it as an introduction to what follows. This passage widens up the use of registers to a range never seen before in the piece. Thus, paving the way for the next part.

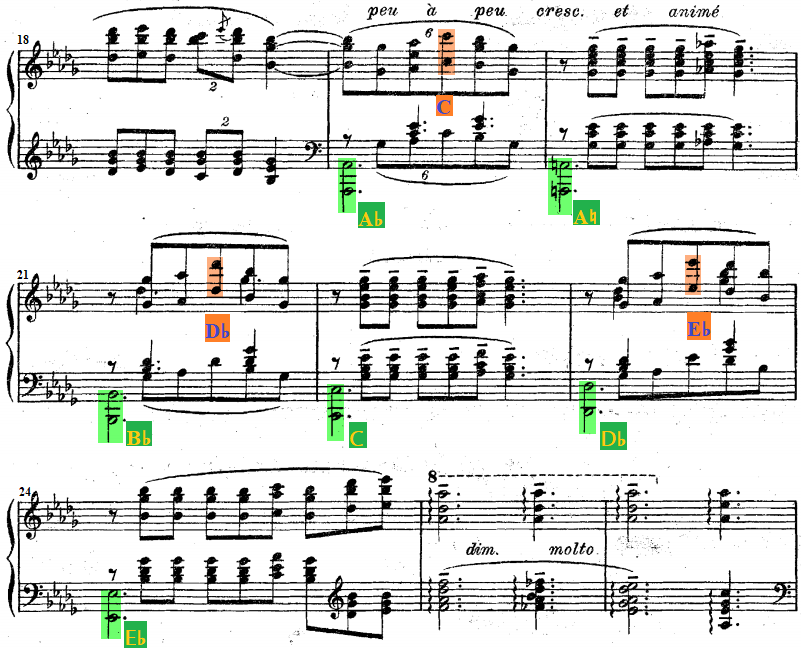

In the second part of the Continuation (Greyish-Yellow in the score, bars 19-24), we can see an obvious development of the motives of the Basic Idea.

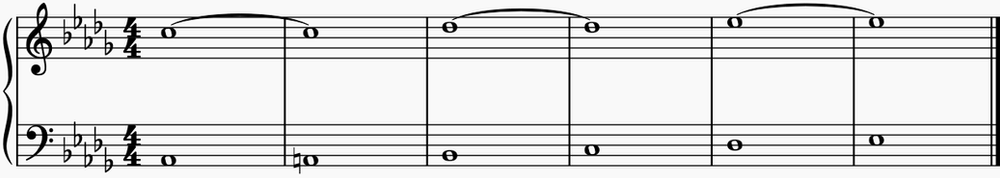

We also observe a sequential pattern of rising notes (the bass moving up stepwise in every bar, as well as the highest notes of the right hand moving stepwise every two bars)

Structural notes isolated:

Also, because of the introductory first Part (Yellow), which had a prolongation of Ebm for four bars, we now have the feeling of Acceleration of the Harmonic Rhythm, which we would miss if the Introduction was omitted. In other words the Harmonic Analysis imposed in bars 15-18 is a single Ebm (with several ornaments), whereas in bar 19-24 we have a different chord in each bar (Ab9, Adim, Gb… etc)

Lastly, in the third Part (Orange in the score, bars 25-27), we have the Cadential Function with a clear liquidation of the chords in an arpeggiated form, further Acceleration of the Harmonic Rhythm, as well as a standard Cadential Progression and a Perfect Authentic Cadence.

Looking back at this 3-Part Phrase, we can interpret the first introductory part as a short of ‘the calm before the storm’. Much like when we perform a crescendo, we often play quieter, even if it is not requested, before we start getting louder, here the composer using the prolongation on Ebm and restraining himself from using too many Continuation or Cadential elements, he made them that much more effective when he did use them in the following Parts.

The composer confirms -in a way- this theory by adding an actual crescendo (‘peu à peu cresc. et animé‘) after the Introduction part, along with the Acceleration of the Harmonic Rhythm and the rising melody to its Climax. This pianissimo first part is only there to make the next part more effective.

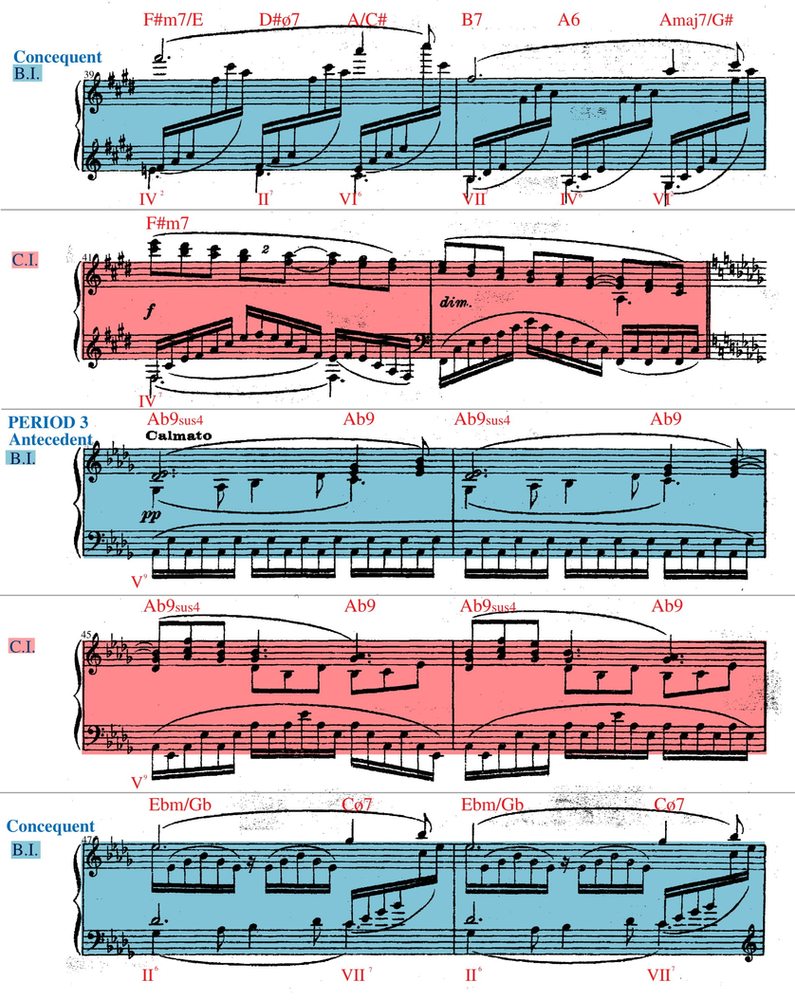

B SECTION

The Second Section is comprised of three regular-sized Periods (8 bars each), all of them using the same 2-bar Basic Idea.

This B Section was difficult to label. Other analysts might reasonably object with the idea of three different themes. The composer does not give many expressive markings to guide us, and the Harmony cannot really help us since there are no Cadential Progressions.

Many of the performers even interpret this Section in various ways. Some might even play it, going against the few expressive marks. However, all of the performances have something in common! They all have a diminuendo and even a ritenuto at the end of every eighth bar to signify a sort of ending, a closure. At the end of the second Period, the composer himself added the diminuendo (bar 42).

This closure by means of Sound is Debussy’s creative way of replacing the traditional closure by means of Harmony (Cadences), which he did utilise in A. This is one of the ways the two Sections contrast one another.

Comparing the three Themes of B, the Basic Idea (Blue in the score) returns every time in a different variation. Sometimes the change is in the Chords (Harmony), the Texture (Sound), even the Intervals (Melody) or a mixture of the above. What unites them, however, is the Rhythm -the most important of all the elements- as well as the direction of the Intervals, even if the Intervals themselves differ.

The Contrasting Idea (Pink in the score) is fundamentally changed every time. There is always use of new material, although some patterns in the elements show an interrelationship.

Even though the Contrasting Ideas do not have much in common, they are all marked in Pink since they all do function as a contrast to the previous idea. Ideally, every time the Pink should have a different shade, but that is a detail we can omit in this analysis.

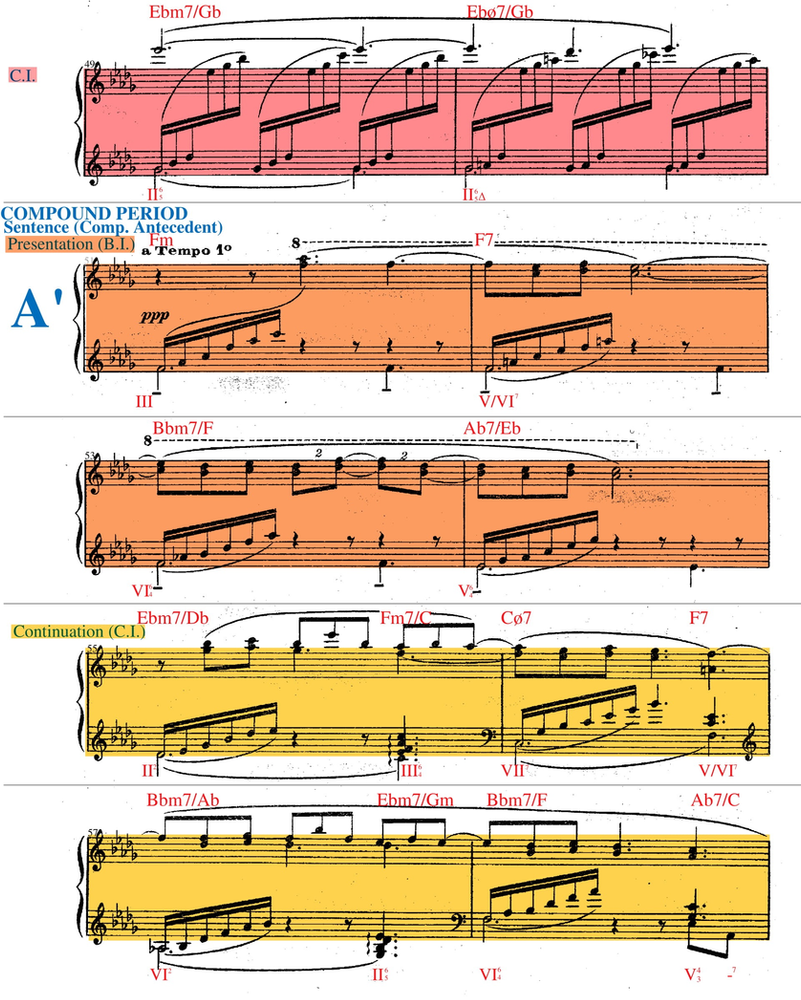

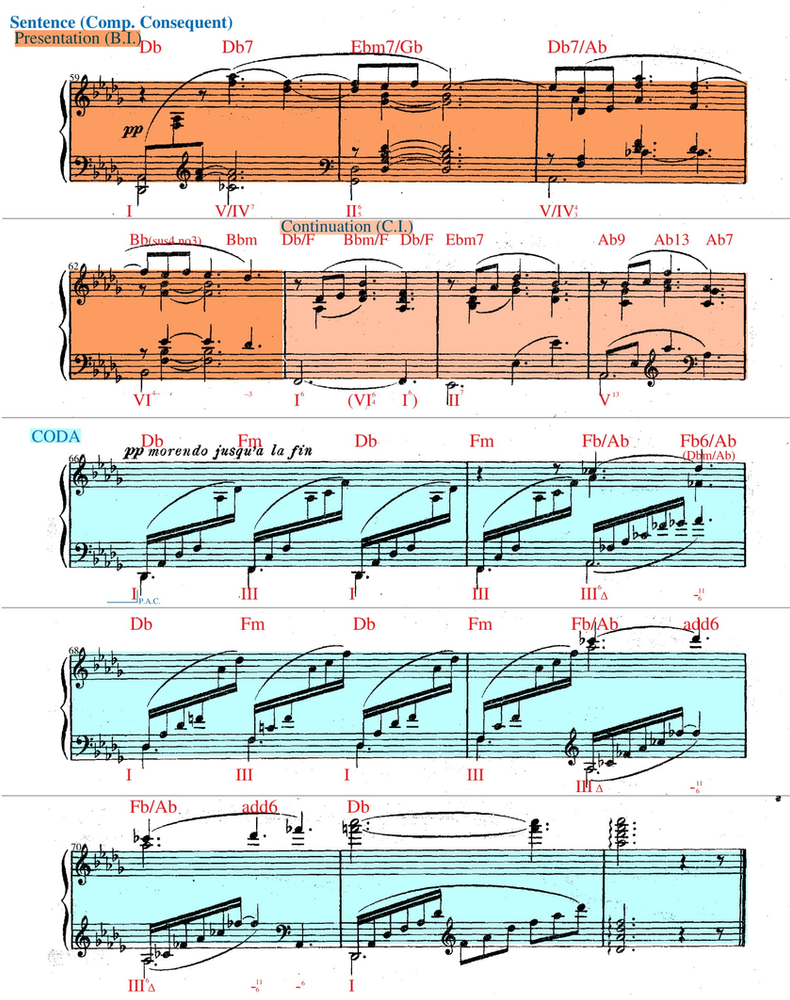

A’ SECTION

For the return of the Compound Period, the composer has made no Formal changes on the Compound Antecedent (bars 51-58), although there are some minor Motivic influences from the B section.

On the other hand, the Compound Consequent (bars 59-72) has a significantly new formation.

This Consequent comprises standard-sized Presentation and Continuation as opposed to the First Section’s Consequent, which was built of an Extended Presentation and an Expanded Continuation.

Specifically, the Basic Idea appears only twice in the Presentation (bars 59-62), in contrast with the triple appearance in the Α Section.

The new Continuation (62-65) is made of single-bar fragments that appear three times. This three-bar-long Continuation seems quite compact, comparing it with the twelve-bar-long one of A.

At the end of the Perfect Authentic Cadence in bar 66, the Coda begins, keeping an elaborate tonic prolongation and giving a satisfactory ending to the music.

Notice that since the piece requires a Closing Section to close, like many pieces, some adjustments had to be made to maintain the balance. By rethinking the Compound Consequent and removing all the ornamental Phrasal Deviations (Extensions, Expansions), the addition of the 7 bars of Coda results in the two Sections, A and A’, being approximately the same size (26 and 22 bars respectively).

If Debussy had not condensed the Theme and restated it in the same size, then the force and the momentum of the music would require a larger Coda in order to effectively slow down and stop the music. The result would be a lengthy and asymmetrical piece of music.

Concluding

The composer’s decision to reimagine the Period provides a fulfilling closure without sacrificing the stability and coherence of the work.

MOTIVIC ANALYSIS

The Presentation/big Basic Idea is the most characteristic part of the piece. It is interesting that it is not overused since it appears only 2 times in A and 2 times in A’.

One of the reasons why the opening is so memorable though might be because it consists of a 2-bar Basic Idea repeated immediately (bars 1-4). In the Restatement of the Presentation, the same idea is played 3 times in a row (bars 9-14). This insistence surely engraves the idea in the listeners’ memory.

Another reason why the opening is so memorable is of course, the unique, original and yet simple characteristics of its motives, which are the building blocks of the rest of the piece.

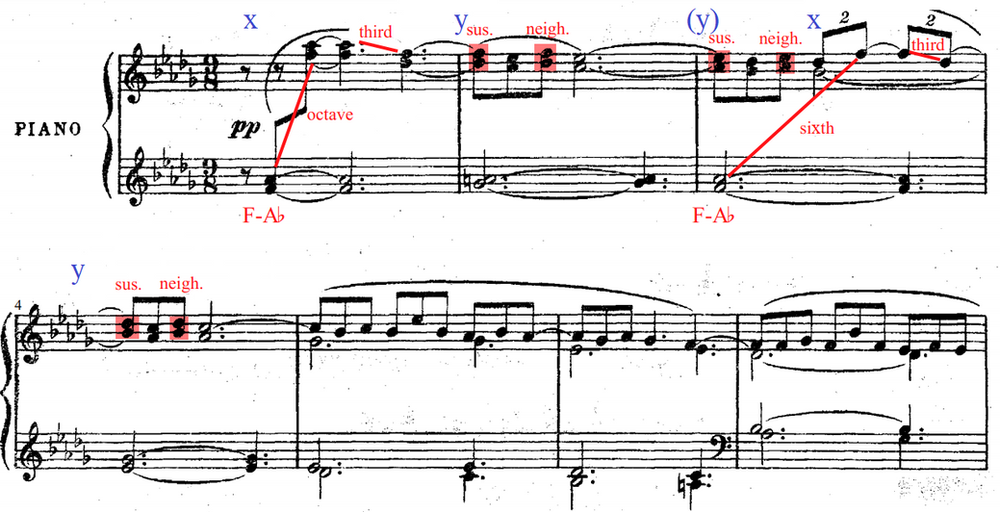

Specifically, the first bar of the piece (motive x) uses a harmonic third (F-Ab) appearing on the second quaver of the first beat, leaping an octave up on the next quaver and skipping a 3rd down on the third beat.

Motive y in bar two is essentially a suspension and a neighbouring note.

All these elements are spread through the motives of the whole piece.

The next time we see motive x (bar 3), not all the elements are the same, but they are varied. The F-Ab enters in the very beginning (not the second quaver), which is a minor difference.

The octave on the second beat is replaced with a 6th, which is presented by a suspension and a neighbouring note. This is the influence of motive y. Finally, it ends with a skip of a third downwards.

(motive y groups backwards/forward)

We notice that most of the elements are more rhythmically varied than melodically. These variations give the piece a feeling of improvisation while it maintaining a motivic coherence.

The next occurrence of motive x (bar 9) is almost identical to the first, only this time we leap an octave twice (or even three times, if you count the first quaver of the bar), changing, therefore, the range, as well as the texture.

Then in bar 11, motive x has a similar variation to that of bar 3 (utilising the elements of motive y), but keeping a more conservative rhythm and intervals. There is also a difference in the range and the texture just as in bar 9.

Finally, in bar 13 we have a mixture with motive y (as in bars 3 and 11), expressed in the wide range and thick texture of this current Phrase (as in bars 9 and 11) again. This time we notice the rhythmical ‘games’ of bar 3.

These motives are further developed in the Continuation. One example is the skip of a third downwards at the end of a motive.

The appearances of motive x in A’ Section are similar to that of A, with some additional elements from the B Section.

Concluding

The gradual addition and variation of elements keeps the interest of the audience, making the insistence on the same musical idea seem as a movement and not as something immobile and rigid.

Even though the ear of the audience is eager to listen to the same tune, again and again, Debussy does fulfil that need, without sacrificing the ‘flow’ of the piece, without risking transforming the ‘waters’ of the piece from a moving sea to a still swamp.

HARMONIC ANALYSIS of Clair de Lune by Debussy

One might think that the ‘Impressionistic’ style of Debussy might require extensive use of Secondary Chords, Modulations and Chromatisms. Although these are certain elements that might aid to that feeling, in Clair de Lune by Debussy, we observe restraint in such tools.

One might quickly object and point out that already from the second bar, we see a Secondary Dominant created with chromatic movement (Adim7). Looking at the big picture, however, we only see such Secondary Chords only four times (bars 2, 6, 20 and 25) in the whole of Section A!

We also observe no strong tendency for modulation. It is safe to say that every chord of the piece can be attributed to D♭ major in one way or another.

The occasional use of borrowed chords (those of D♭ minor, marked with Δ) or secondary chords are not enough to change the tonality, but merely to decorate and ‘colour’ it.

So What Makes Clair De Lune Impressionistic?

Of course, the Texture and the Rhythm have a big effect in regard to the style, but Harmony is also one very strong factor. We can observe its impact in two ways.

The Inversions of the chords is the first obvious way the Harmony aids the style. In the First Section, one would struggle to find a handful of root position chords.

The first, second and even third inversion chords create a constant unstableness, resembling the blurriness and unclear shapes of the paintings of Impressionism.

However, in the Cadences of the A Section (bars 8 and 26-27) we encounter root position Dominants and, in the Second Cadence, a root position Tonic.

It is just like Impressionists’ paintings, where the objects within the work have unclear boundaries and no straight lines, but the work itself is framed in a perfect, Euclidean rectangular. Similarly, Debussy frames his work with Classical, Perfect Cadences.

The Seventh and Ninth Chords are the second harmonic tool that defines the style. Looking at the First Section, we encounter only a few simple Triads.

The characteristic of the Seventh (and Ninth) Chords is that they contain a chord within a chord. In the third bar, for example, we have a B♭m7, so a B minor and a D♭ major simultaneously. This ambiguity in the character of most chords enhances the uncertainty of where we ‘step in’, when we move from chord to chord.

One of the occasions that the composer consistently chooses not to be ambiguous is at the Tonic Chords of the Cadences (and for that matter, every Tonic Chord) and decides to use them as Triads in root position. Again, the boundaries of the musical painting must be clear, and this piece is ‘enclosed’ in the key of D♭ major.

We share with you this beautiful performance of Clair de Lune by Debussy, played by Khatia Buniatishvili.

If you are interested in learning how to analyze classical music, join our courses in London or online. More info.

START YOUR FACE TO FACE OR ONLINE PIANO LESSONS WITH US