Music Theory Resoucers, Uncategorized

Evaded Cadences

Definition

The failure of an implied cadence to reach its goal harmony. The event appearing in place of the final tonic groups with the subsequent unit and (usually) represents the beginning of a repetition of a prior continuation or cadential passage.

by William Caplin

Essentials about the evaded cadence

“Backwards Grouping”

“In the case of the deceptive cadence the arrival chord groups backwards.”

What does that mean?!

It means that what comes after the arrival chord is totally disconnected “harmonic-progression-wise” with the final chord.

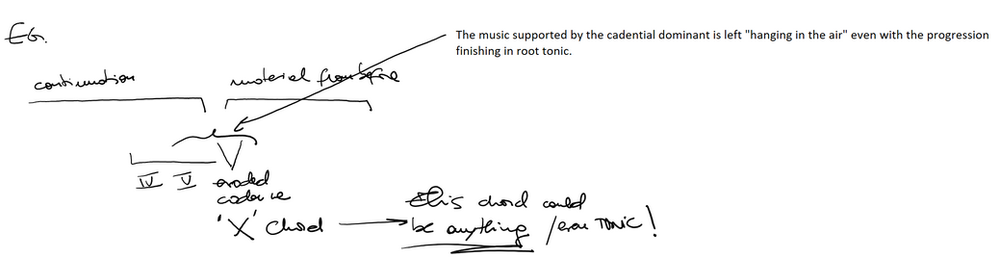

The chord of arrival could be ANYTHING!

The evaded-cadence grouping works exactly as opposed to the grouping of the deceptive-cadence. The new material STARTS! with the arrival chord; therefore we say it, groups, forward.

The evaded cadence, by bringing material that “backs up” projects a sense of “let’s try this one more time and see if we can finally make it to the end”.

In Caplin’s words:

In the case of the deceptive cadence, the musical event supported by the harmony that replaces the final tonic belongs entirely to the ongoing cadential process; it thus functions as the final event, the goal, of the phrase.

Like an authentic cadence, a deceptive cadence has a distinct moment of arrival, after which the subsequent phrase begins. The event that follows the cadential dominant groups backwards with that dominant (and with the rest of the cadential progression).

The latter is particularly clarifying as it explains the syntax of the deceptive cadence itself.

On the contrary, the evaded cadence arises when everything is prepared for the final event to arrive (at some clearly predestined moment in time), yet the sense of a goal event fails to materialize.

Instead, the event that appears where the goal was expected to occur is not heard as belonging to the ongoing cadential process; rather, it belongs already to the subsequent phrase. In other words, the event that follows the cadential dominant groups forward with the next phrase, thus creating a salient disruption in the grouping structure, because the cadential group fails to finish before a new group begins.

This sense of grouping disruption is what allows an evaded cadence to arise even if the cadential dominant literally resolves to a root-position tonic. That tonic is heard not as an ending tonic but rather exclusively as a beginning tonic. (If it was heard as both a beginning and an ending simultaneously, then an elided authentic cadence would be created).

More powerful compared to IAC or “Abandoned Cadence”

The evaded cadence makes a considerably more dramatic effect than an IAC or an abandoned cadence.

The evaded cadence makes a considerably more dramatic effect: the imminent closure of the theme is thwarted at the last second and then quickly attempted again. The lack of any event representing formal closure, combined with the breaking off of a highly goal-directed process just before its completion, arouses a powerful expectation for further cadential action.

In the abandoned cadence, the effect is less pronounced as the harmonic progression tends to lose its sense of direction and therefore the music tends to wander off somewhere else before returning on track toward another cadence.

Paramount concepts and one exception

- Evaded Cadence is one of three cadential deviations -abandoned cadence, deceptive cadence and evaded cadence-

- Evaded Cadences rarely appear in simple main theme contexts. They much more often appear in Subordinate themes and other loosely organised sections of the sonata or other full-movement formal types.

- As opposed to the abandoned cadence, in the evaded cadence the dominant is locked into root position. The problem is only the absence of an event associated with the final tonic. There are certain exceptions -explored below-EXCEPTION

When we label abandoned cadence we normally back up the idea on the dominant being inverted.

Nevertheless, sometimes happens that the root position dominant moves to V24 before proceeding to I6 to create an EVASION.

In e.g. 9.3 p. 269 -book paging-, we can see how the V24 can be understood as an embellishment of a root position dominant. This 7th -Db- is used as a passing note towards Do. Then we in e.g. 9.3 we see Eb -bar 35-, Db -bar 36-, C -bar 37-.

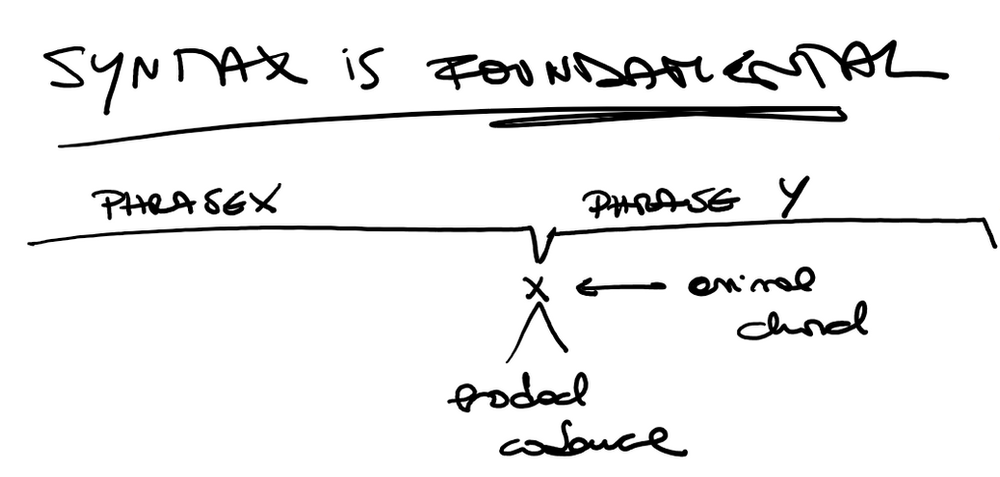

Syntax is defining

The change in syntax can be characterized by a change in:

- Texture

- Dynamics

- Accompanimental patterning

- Melody

- Register

These factors can happen independently or simultaneously.

The melodic line is usually interrupted in its projected resolution to the tonic or -rarely- third scale degree.

It sometimes leaps to the 5th scale degree to then start another descent to the tonic in subsequent cadential passages.

Other times, melody leaps to the tonic but in a different register so the normal stepwise resolution is avoided.

Even if the melody resolves as expected, the sense of evaded cadence can still be projected by means of the aforementioned resources.

Four very important points:

- Caplin talks about two phrases, the ongoing one and the extension phrase that will be originated by the use of the evaded cadence.

- The new phrase will begin with the arrival chord of the evaded cadence

- The arrival chord of the evaded cadence will exclusively work as a beginning chord of the new phrase. If it was heard as beginning and end of the two phrases we would be facing something different to an evaded cadence, that would be an “elided authentic cadence”

- By all means, the syntax is fundamental.

It is so VERY important that the arrival chord of the evaded cadence could even be a root tonic! The latter would have closed a PAC -harmonically speaking-, yet the syntax would be so strongly projecting non-conclusion, that yet the arrival chord, in this case, the root tonic, would NOT be considered ending of the ongoing phrase but JUST the beginning chord of the new phrase.

Evaded cadence and Subordinate theme

Evaded cadences are used quite often to dramatize the final PAC of the subordinate theme both in the exposition and recapitulation of the sonata form -mainly used as loosening devices that effect structural lengthening-. Evaded cadences are often used in conjunction with “one more time technique”.

This effect is particularly well suited to subordinate themes, since dramatizing the subordinate key is a principal aesthetic objective of the classical style. Establishing the subordinate key as a foil to the home key is made all the more effective if the struggle to gain its cadential confirmation is hard-won.

The use of evaded cadences is the most common way to extend cadential function in subordinate themes.

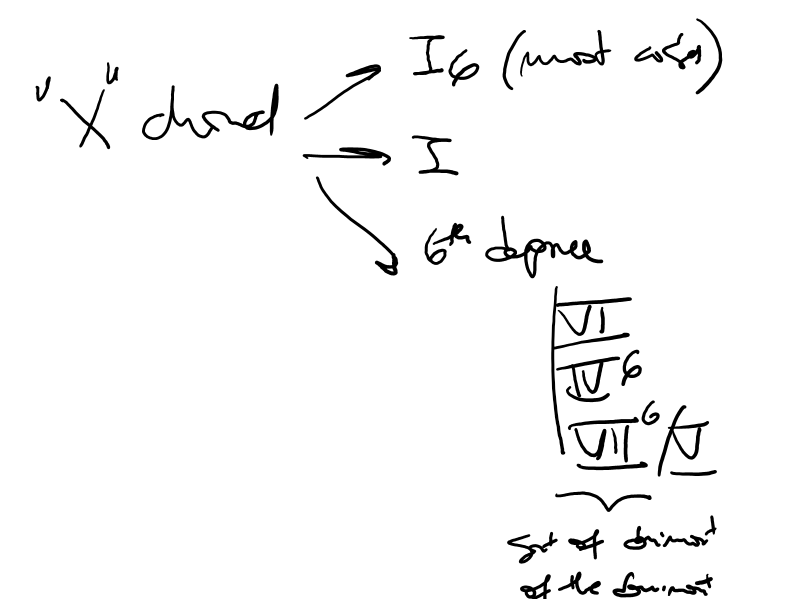

In most cases of evaded cadences, the cadential dominant moves to I6 which distracts the listener from feeling the cadence resolving at that point. The I6 is particularly useful as it might be used as the beginning of another cadential progression, one that can be evaded again or may finally bring an actual cadence. In order to facilitate the ending on I6, the cadential dominant may move to V24 just prior to the cadential evasion.

Some possible chord resolutions

Examples from the literature

Mozart, Piano Sonata in C K309, III, 13-19 / p. 142 -book pagination-

The theme is set up to close on bar 16 but it is precisely there where we head back to the material on bar 13.

The chord of arrival is the root tonic, yet the syntax is clearly not reinforcing the sense of closure. Caplin says: “The tonic groups forward, not backwards”, I add: “it groups with the following phrase”.

ONE MORE TIME TECHNIQUE

The “One more time technique” was termed by Jannet Schmalfeldt specifically in reference to the “evaded cadence”.

Nevertheless, the latter term can also be used after an IAC which can ignite a “lead-in” that presents a repetition of previous material like in example 5.11 page 139 -book pagination-, after a deceptive cadence or after an abandoned cadence.

Besides this terminology, the important concept is that UNLIKE other “cadential situations”, an evaded cadence marks such a disruption of the grouping structure that makes the “one more time technique” even more noticeable and dramatic.

Mozart, Piano Sonata in F K280, I, 1-13 p. 142 -page 139 book pagination-

In this example, we can see how the evaded cadence helps the incorporation of an extension.

Haydn, String Quartet in B minor, Op. 64, No. 2, I , 21-30 p.390 excerpt starting on bar 21 / e.g.12.6

The sudden change in texture and mode -major to minor- together with the bass leaping a third-down-setting the I in the first inversion, I6- contributes to the cadence evasion.

In this example the material following the evaded cadence is new. Nevertheless, the evaded cadence could have brought previously heard ideas using the “one more time” technique.

This evaded cadence is followed by an abandoned cadence on bar 32 prepared by the downgraded dominant V56 in bar 31. The abandoned cadence is followed by a resolving ECP on PAC.

Haydn, Piano Sonata in C, H. 35, I, 36-67 p. 392 excerpt starting on bar 56 / e.g. 12.7

The cadential idea beginning on bar 58 is evaded at bar 60 promoting its repetition. A PAC is finally achieved at bar 62.

Beethoven, Piano Sonata in F minor (“Appassionata”), Op. 57, iii, 64–96 p. 402 -book paging- excerpt from bar 79.

Here we can see an evaded cadence showcasing Neapolitan IIb6 as arrival chord.

Haydn, Piano Trio in C, H. 27, iii, (b) 66–7 page 533 -book pagination-

This is a good clarifying example of why this should NOT be labelled evaded cadence. Though the tonic arrival on bar 21 ignites the repetition of a previously heard element, yet we still feel the sense of closure produced by the PAC. Therefore, it looks far more attained to label the segment starting at bar 21 “closing section”. The subsequent quavers feel more like an “ornated ending” than the incidence of new material.

Mozart, Piano Concerto in E-flat, K. 482, I, 50–76 page 675 -book pagination- excerpt from bar 58

A typical example of evaded cadence used on I6 and chained to extend the theme via the “one more time” technique by Janet Schmalfeldt.

OUR ONLINE LESSONS ABOUT EVADED CADENCES

https://youtu.be/lYR47wmNXmUhttps://youtu.be/DxBhTGfxx-shttps://youtu.be/zx_cR2Zmrgchttps://youtu.be/UxBEjCgbPUUhttps://youtu.be/HyS_-UV2-R4

All examples are taken from William Caplin’s – Classical Form – Oxford University Press

In order to see the examples, we strongly recommend the purchase of the book http://www.music.mcgill.ca/~caplin/analyzing-classical-form.html