Uncategorized

Classical Music Analysis – Extensions

DEFINITION

William Caplin’s definition of extension centres around two main facts:

- Extra Material is incorporated in the formal functions producing an elongation

- This extra material is not “necessary” to express the function and therefore -sometimes- a subtraction can be practiced to simplify the phrase.

GENERALITIES

We talk about an extension when, for example, fragments of a continuation are repeated far more than what is necessary to express the function.

If something is there in excess of the expression of the function, then we are in sight of an EXTENSION.

- “Extension” is certainly more used in the repertoire than “Interpolation”

- Extensions contribute to producing less tight-knit structures. This directly affects its application.

For example, extensions:- are one of the loosening devices used in the Subordinate Theme.

- can be present quite often in the B section of the Small Ternary theme and far less often in the Small Binary.

- can be seen inscribed within a harmonic sequence. The latter is much used in solo parts in the concerto form and rarely in its ritornello.

- In the opening ritornello -informally called the concerto “orchestral introduction”-, there is little reason to produce extensions due to the stable content within it.

- are usually seen in main-themes of first-movement-sonata-form

- The standing on the dominant is an “extension” indeed

- The main difference between extension and expansion is the fact that an extension requires an “addition” of material while an expansion is about “swelling” the function itself.

- The main difference is that the EXTENSION takes part in the ongoing formal function while the interpolation doesn’t.

- Extensions are widely used in the “Theme with variations” They are mainly deployed near the end of the piece. See example VIII for further clarification.

- CODAS are particularly receptive to extensions -as well as to expansions”. Being loose devices, they benefit from the use of elongating “phrase deviations”

- All cadential deviation and IAC can foster extensions.

EXAMPLES

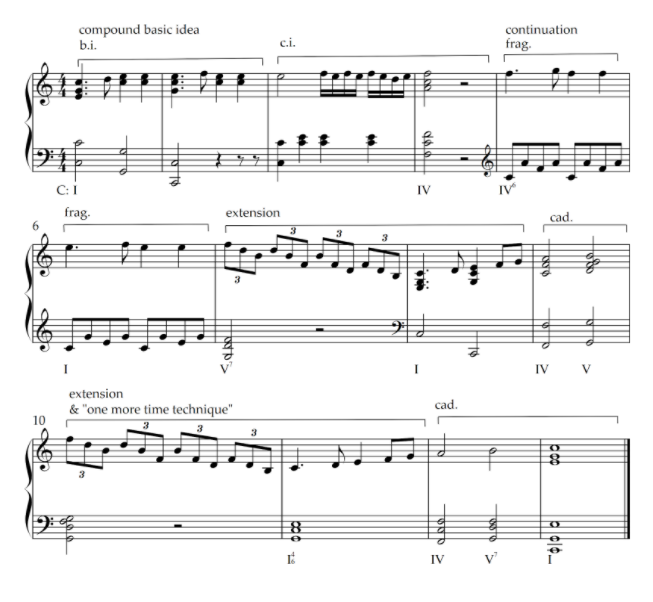

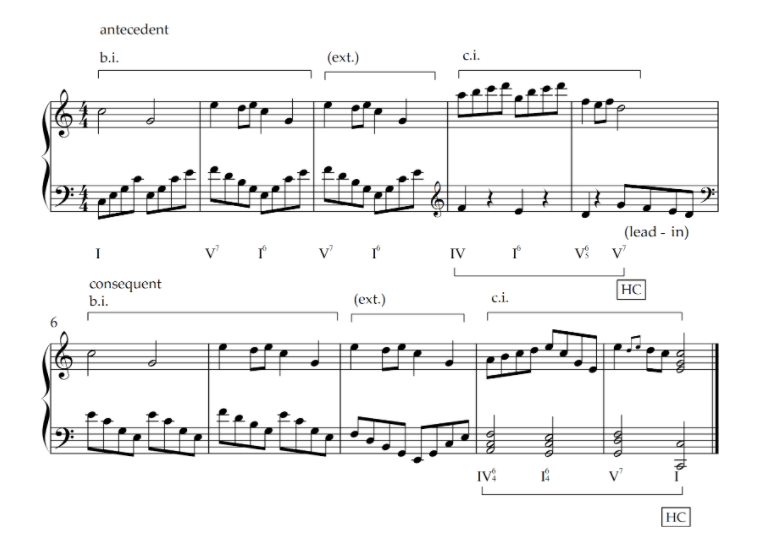

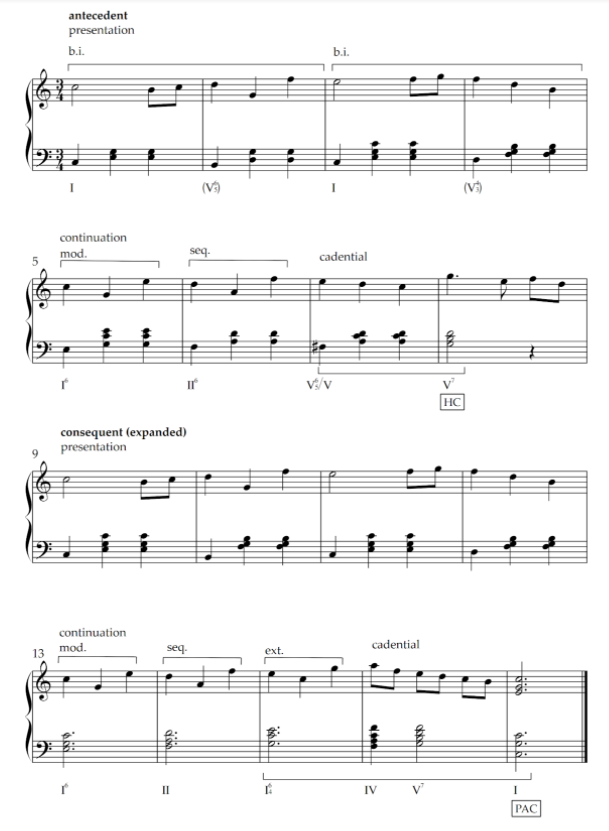

I. The continuation shows an acceleration of surface rhythm in the extension material and harmonic acceleration in the Cadential episodes.

In the case of this extension, we can see how it would be quite easy to suppress it without affecting the function itself.

II. This example shows a very simple method of extension; the repetition of a motivic element of the b.i.

III. In this example, we can see how the antecedent is extended by adding an extra bar dedicated to the deployment of dominant harmony. On the other side, we also practice an expansion to the Cadential function.

This exercise shows clearly the difference between an extension and an expansion.

IV. In this example, we see how the consequent of this compound theme is expanded through extending the continuation prior to the cadential.

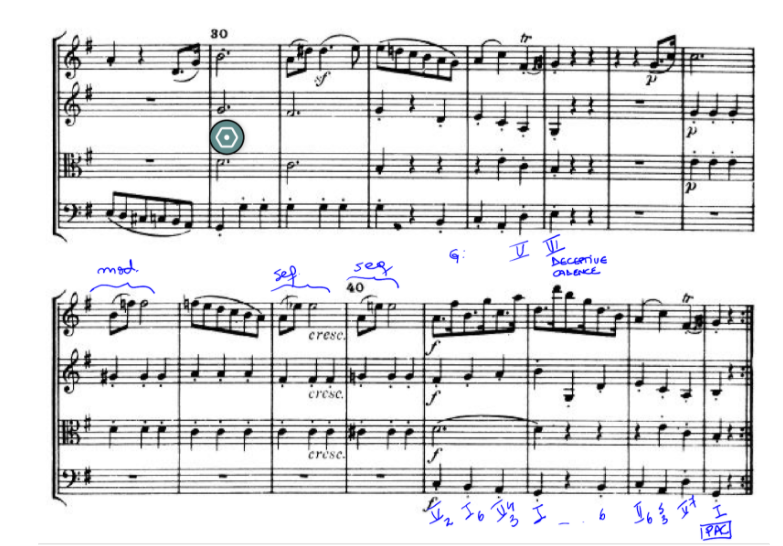

V. Some other functions can also be considered extensions. The standing on the dominant for example can be seen as an extension of the V.

A good example is Haydn Piano Sonata in G, H 39, I, bars 28 to 32.

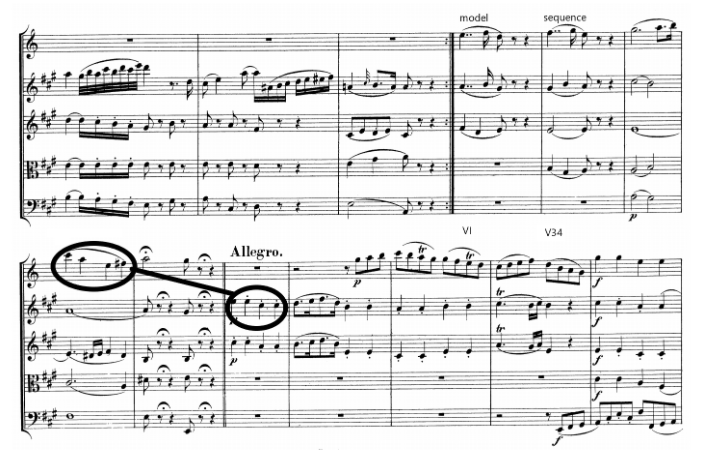

VI. Mozart, Symphony N. 40, iii, bars 1-17. This extension is perpetrated by augmenting the length of the sequence within the continuation.

VII. Haydn, String Quartet Op. 54 No 1, iii, bar 33…

In this bar, we can see how the phrase is extended through the use of the “model-sequence” technique after a deceptive cadence.

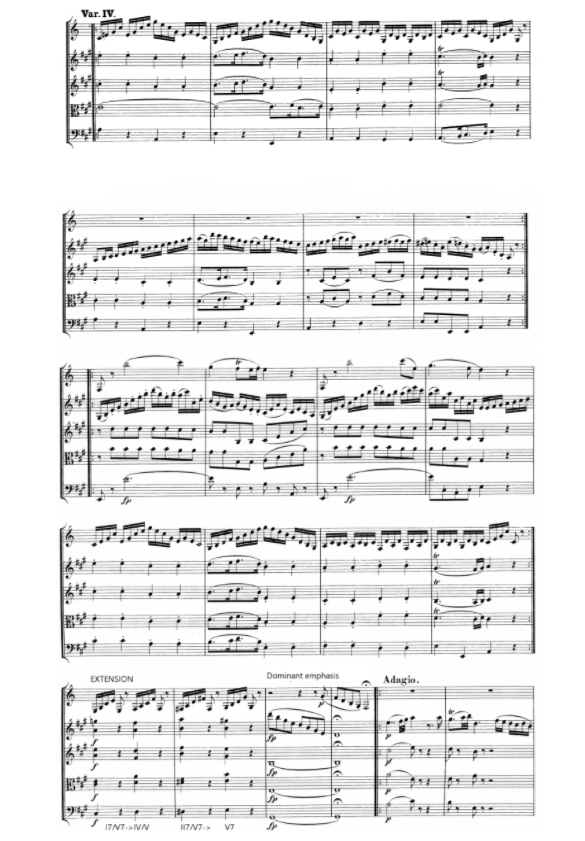

VIII. We find another interesting example in Mozart’s Clarinet Quintet in A, K 581, iv.

The extensions used here help the blending of the last sections. The variations depict a very similar structure: “Small Ternary”.

A. In the first instance, Mozart applies an “extension” to variation IV which helps to transition to the “Adagio section”.

Variation IV is showcased complete; a small ternary.

The extension is built as a “continuation” phrase starting on an ascending diatonic harmonic sequence which leads to a short development of the dominant.

We cannot label this “dominant arrival/development of the dominant” a ”standing on the dominant”, the main reason: There is no cadence prior to the “dominant emphasis”.

At the same time, the arpeggiation on the sequence is derived from focal material from the variation itself.

The augmentation is the perfect tool, to efficiently bring the rhythmic “drive” down and set the basis for a “smooth entering” in the Adagio section.

NOTE:

See we called this musical moment “Dominant emphasis”, “Dominant arrival” and “Developed dominant”.

We could order these terms and say: The sequence ends on a dominant arrival, after which we can see a clear emphasis on the dominant by means of developing the motive syntactically into an augmented expression on the contrary motion of the successive arpeggiations seen immediately before the dominant arrival itself -the later accounting for developing of the dominant.

B. Mozart uses “extension” one more time before the last “recapitulating” section.

In this case, the sequence is built up as a continuation phrase, the same as before with one main difference: he reaches a “Half Cadence”.

Why can we say in this case that this is a “Half Cadence” and not a dominant arrival?

Mainly because this dominant is not reached as a part of a sequence as per the previous immediate example. In this case, we can see the Dominant reached at the end of a two-bar component which both harmonically and syntactically prepares the music for a “closure” on the dominant.

The continuation starts with a two-bar model sequence following a descending diatonic harmonic progression. The harmonic sequence is 100% clear, though we can see these attributes expressed in the diatonism between the two focal harmonic points.

The last section of the continuation includes a “cadential function” reaching a fermata aligned with the half cadence which then leads to a second fermata on the last rest of bar 104. All the latter intended to stop the musical flow and to create the right conditions for the “recapitulating” last section.

We could track the motive sequenced to the melodic line of the rhythmic motive in unison of bar 2 at the beginning of the “Andante con Variazioni”. Though remote, the similarity is there.

One bar prior to the fermata we can see how Mozart uses the same rhythm he deploys at the beginning of the next section -the main theme-. The latter strategy is very efficient as it both, creates the right conditions for the musical impulse to slow down, while it anticipates the material deployed in the next section.

The material is public domain and extracted from IMSLP. See link below