Music Theory Resoucers, Uncategorized

Pachelbel’s Canon in D – Complete Analysis

Full Analysis of Canon in D Major by Johann Pachelbel.

Canon in D – Complete Analysis

Canon in D – Complete Analysis

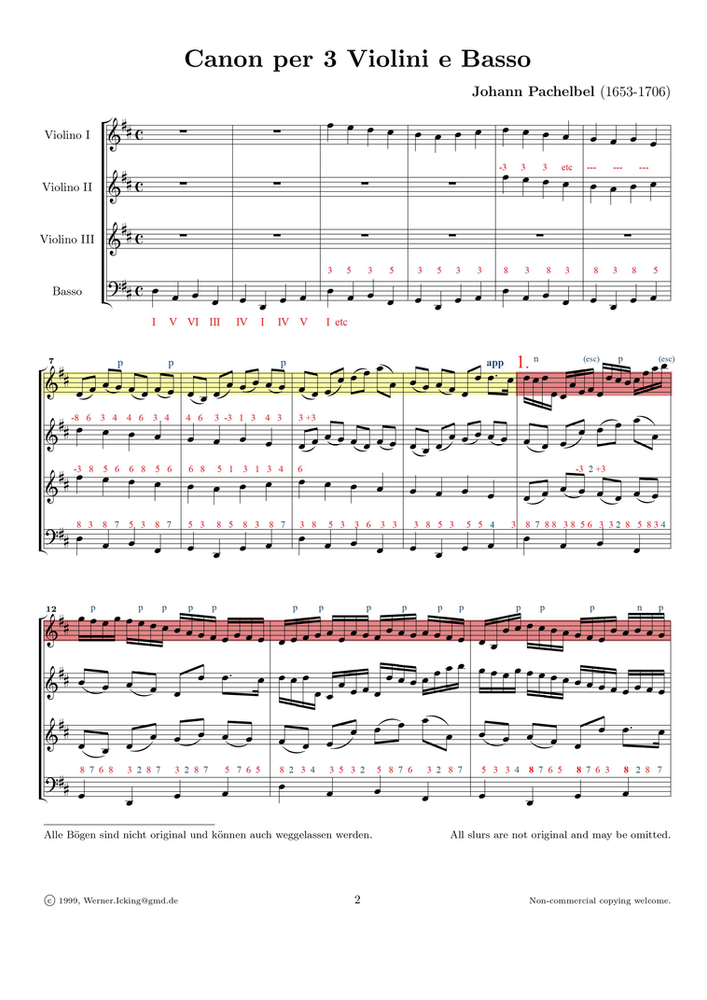

The piece is a Triple Canon at the Unison, with a constant rate of two bars. This means that every motive is played three times, once on each of the three violins.

In fact, all three violins have essentially the same score.

The Violin I starts first (bar 3), two bars later Violin II (bar 5) and two bars later Violin III (bar 7).

This means that each of them has the Lead on some moments, while it Accompanies on other moments.

The Canon is only interrupted on the last bar of the work, so that all three violins end simultaneously.

BRIEF ANALYSIS of Canon in D

The strict Cannon, which Pachelbel chose to compose on, not only allows the composer to foresee the form, but also demands of him to plan ahead.

In order to create a structure that works, the composer chose texture and density as his main tool, since the harmony could not be altered. Four bars present fast-paced activity (Lead Motive) and in the next four bars, they gradually disappear in the background (Accompaniment). Every Cycle of 8 bars is a sort of breath-in and breathe-out.

Moreover, the Cannon is a technique that demands to move forward to new material, once a Cycle is done. When all three violins have played a motive and its counter motive, it is safe to say that one’s ear is saturated by that motive and craves something new.

However, almost all motives have in common two simple elements that unite them together.

The leap of octave and the neighbouring note. That is Pachelbel’s way of moving forward to new material, without losing the consistency!

On top of that, there are some rhythmic elements that appear, disappear and reappear.

Cycle 1 introduces the semiquaver rhythm, which we hear again in Cycle 3. Similarly, Cycles 2 and 4 share the demisemi- and semiquaver rhythm.

This playful rhythmical-motivical braiding makes clear that the Composer does not compose the themes ‘as he goes’, but he must have had planned ahead.

Concluding, for any type of composition, structure and consistency are essential.

The harmonic cadences that would mark the end of a Phrase, are here replaced by textural condensing and loosing processes to mark the end of a Cycle.

This option -to give structure, being less relied on harmony but texture- is something that many contemporary composers can benefit from.

In other works, elements or whole motives and ideas are free to return or be reinterpreted freely. In a cannon like this, the composer must be very cautious not to bore the audience while, at same time, he presents a solid piece.

The solution given by Pachelbel is tiny elements, such as the Octave Leap and the Neighbouring that recur discreetly and creatively throughout the piece, and other rhythmical elements that unite some parts and distinguish them from others. All this give to the music the desired consistency, without boring the audience’s ears.

DETAILED ANALYSIS of Canon in D by Pachelbel

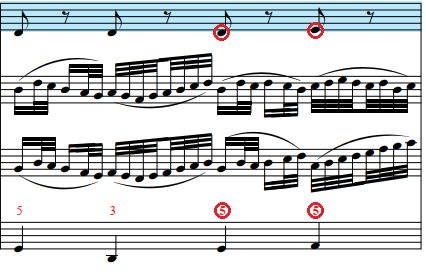

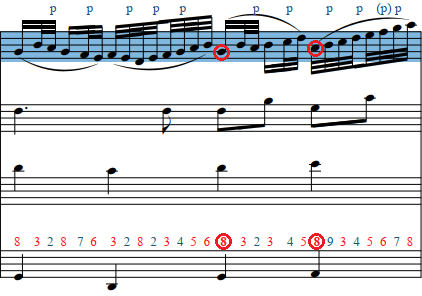

Harmony/Counterpoint

The bass (usually Cello), only has a 2-bar part, which sets the harmonic progression. The same two bars are repeated in a loop throughout the piece. It is therefore an element that the composer himself decided not to develop or even be able to change fundamentally.

It is interesting to mention that, although the bass notes never change, the chords might be slightly reinterpreted. For example, up to bar 16, the fourth chord is an F#m (III). On bar 17, however, the first violin plays D, so the chord is interpreted as a D/F# (I6).

On the score, all the consonants between the First Violin and the Bass are explained. They are mostly neighbouring and passing notes.

The ones in a parenthesis are consonants that could be considered non-harmonic

In the first 25 bars, the intervals between the Bass and First Violin are given. Many ‘forbidden’ intervals are revealed. Such are the parallel fifths on beats 3 and 4 in bar 25 which are hidden on the background, behind the busy Violin II and III.

Another example is the parallel octaves between beats 3 and 4 in bar 20. Here, the dense melodic line conceals the error.

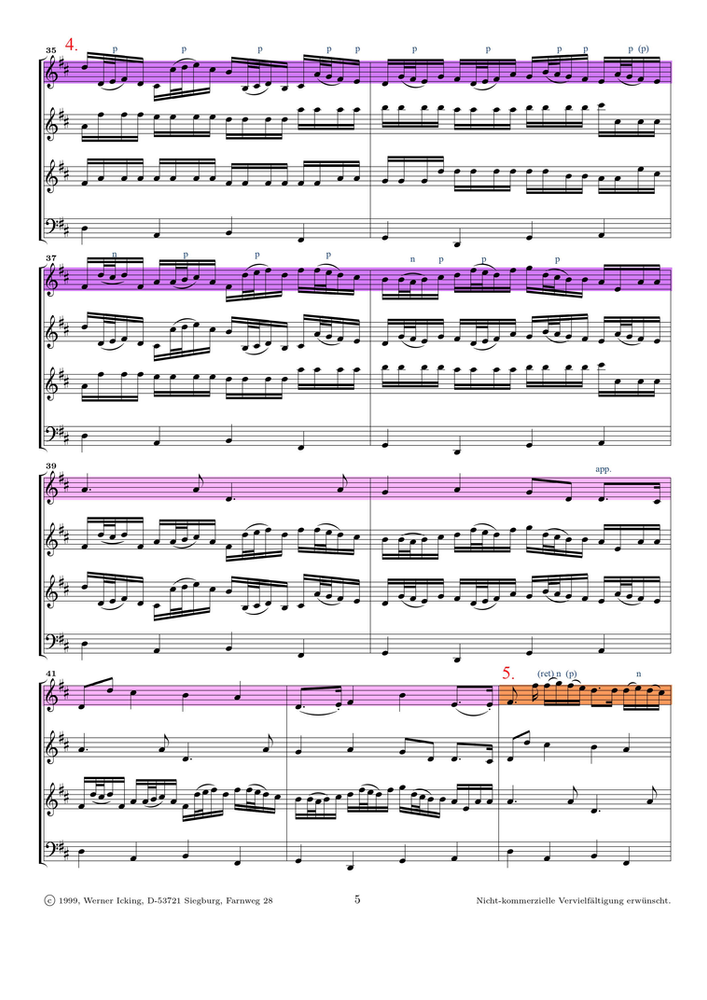

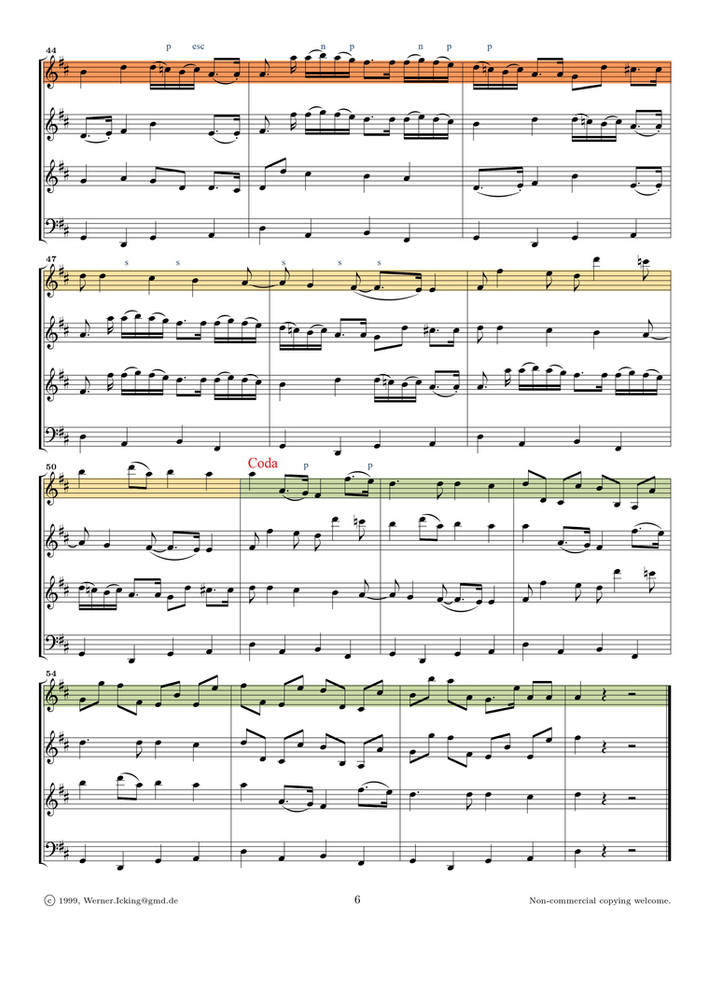

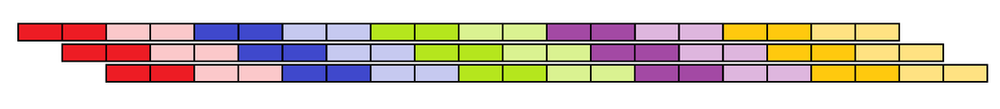

Formal Structure of Canon in D

Each Cycle lasts for eight bars, which is divided in two parts, the Lead and the Accompaniment (four bars each).

The Lead is itself divided in the Primary Motive and the Secondary Motive (Lead 1 and Lead 2 in the image below), each of them lasting two bars.

In practise, we always hear part of the Lead being played in one of the violins.

One of the main differences between the Lead and the Accompaniment is the use of dissonances.

In the Leading part we encounter varied types of non-harmonic notes created from the various motives of each Cycle.

On the other hand, the Accompanying part has few if any non-harmonic notes, since it functions as a ‘cleansing of the palate’, so to speak.

VERY DETAILED ANALYSIS of Canon in D

Intro:

Bars 1-10 are essentially an introduction, the ‘Curtain Opening’.

Bars 1-2 set the ‘scenery’ of harmonic progression.

Bars 3-6 thicken the texture, introduce the characters-instruments, using only ‘safe’ intervals of 3rds, 5ths and 8ves.

Bars 7-10 thicken the surface rhythm with the addition of occasional non-harmonic notes.

The passage ends with an appoggiatura (D-C# bar10), usually performed with a trill. This characteristic appoggiatura initiates the first Cycle.

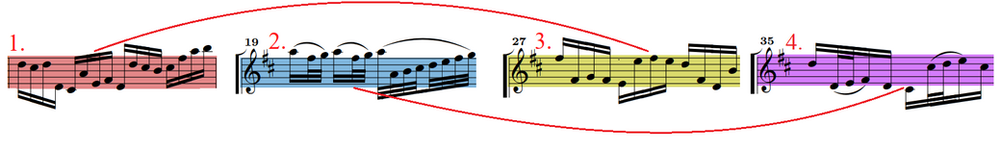

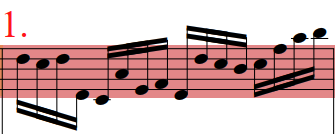

Cycle 1 (Red):

Bars 11-18

Bars 11-12 are the Primary Lead Motive.

Here we see an acceleration of the surface rhythm, utilising a constant rhythm of semiquavers.

The neighbouring note and leap of octave, with which the motive enters, are two very characteristic elements that recur in this piece.

Bars 13-14. The First Violin now plays the Secondary Lead Motive, complementing the Primary Motive performed by the Second Violin. The Primary is -for the most part- played lower than the Secondary, ensuring that the former stays on the foreground.

Bars 15-18 are the end of the First Cycle, where the first violin introduces the first Accompanying Motive. It returns to the longer values of crotchets and quavers, while it loosely uses the first elements of the Cycle (leap of octave and neighbouring note).

It is worth mentioning that, although the Accompaniment is in a high register, it does not ‘steal the limelight’ from the Leading Melody, but stays in the background. The composer achieves that by means of Rhythm. The shorter values, which demand our attention, appear on the Lead.

The performers could enhance the effect of foreground-background by means of dynamics, playing the Lead louder, but it is not necessary.

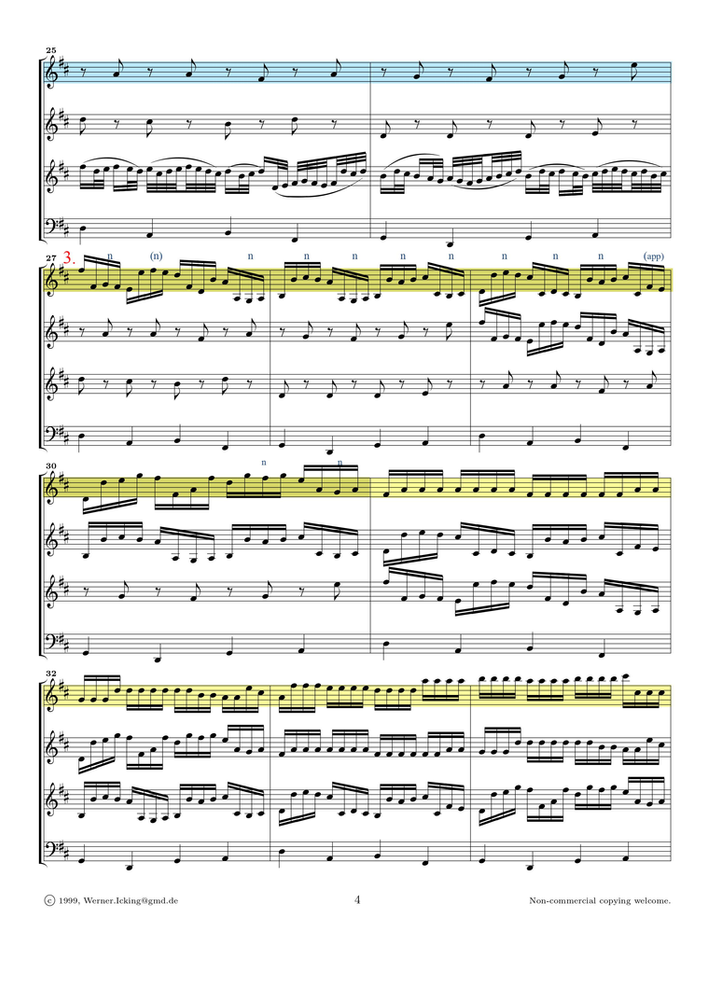

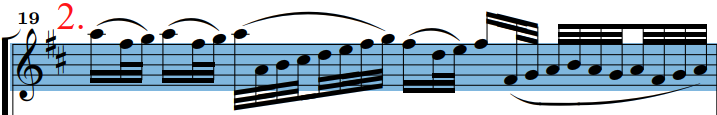

Cycle 2 (Blue):

Bars 19-26 are the most famous part.

Bars 19-20 introduce the new motive.

This time, even shorter values are used (demisemiquavers and semiquavers).

The standard passing notes are used to connect the structural notes, while the special elements of neighbouring and leap are rarely used.

There is a smart use of the octave leap in bar 19, which changes the register, creating two levels in the melody. This provides several effects, one of them is that Pachelbel keeps the audience’s attention by surprising them.

Bars 21-22. Following the rules of the canon, the Second Violin takes Lead 1, while the First Violin moves to Lead 2.

This Secondary Lead compliments the Primary even smoother than that of Cycle 1. We observe mostly doubling 3rds, above and below. The two violins virtually never go against each other in this Cycle and generally move in parallel motion.

Bars 23-26 lay out the gradual fading out of the second motive. The First Violin introduces the Accompaniment, which is even more reserved than before.

Here we see only quaver notes on the strong parts of the beats first (23-24) and then on the weak parts (24-25).

We see the use of the octave leap once (bars 23-24)

It is worth mentioning that on the last two bars (24-25), the Leading Melody on the Third Violin is not the Primary, but the Secondary/doubling 3rds part. It can still give the impression of a distinct, independent motive.

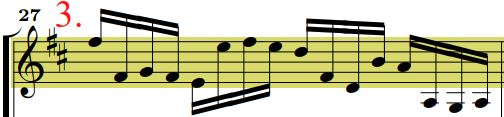

Cycle 3 (Yellow):

Bars 27-34

Bars 27-28. The composer uses the previously mentioned neighbouring note and leap of octave to create this motive. It is made, almost exclusively, of these two elements.

The result is a melody changing always between two levels. Essentially there are two melodies that appear and disappear successively, creating gaps every crotchet beat. This is what we call Oblique Polyphony.

Notice that Pachelbel only uses semiquavers, as in the First Cycle.

Bars 29-30 these gaps are filled in the first bar, while enhanced in the second.

In other words, in bar 29 Violin I plays in the range opposite to Violin II constantly overlapping each other. In bar 30, Violin I is constantly a 3rd or 6th above Violin II, doubling and enhancing the contrast between the layers.

Bars 31-34. This is the only time that the rhythm of the Accompaniment is the same as that of the Lead. However, the constant semiquavers are repeated notes, and therefore avoid any dissonances.

It is very interesting to mention that, in complete contrast to the previous Cycle, in these last two bars (33-34) the Lead has been moved to the Background, while the Accompaniment is rising to the Foreground.

Lead 2 was formed as a complement to Lead 1, without which it cannot compete against the Accompaniment part of Violin I and II. The rising semiquavers of Violin I, especially, overshadow Violin III and this is often exaggerated by a crescendo on the First Violin.

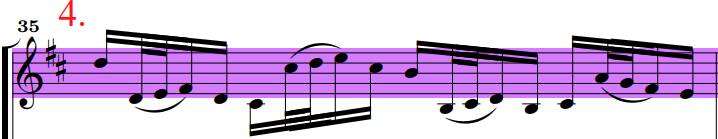

Cycle 4 (Purple):

Bars 35-42

Bars 35-36. The Lead is related to the previous Cycles.

This lead shares the rhythm of the second Cycle (demisemiquavers and semiquavers).

It also shares the constant leaps of octaves, and other intervals, with the third Cycle.

Bars 37-38. Just like in Cycle 3, here the second part of the Lead is initially playing in opposite registers to Lead 1, while on the second half it moves parallely.

Bars 39-42. The Accompaniment returns to the longer note values (crotchets and quavers) resembling a lot the Accompaniment of the First Cycle.

The only dissonance is an appoggiatura at the end of the first half (bar 40).

Also, notice the leap of octave in the beginning of the second half (bar 41).

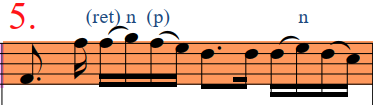

Cycle 5 (Orange):

Bars 43-46

Bars 43-44 start with a new motive of a dotted quaver-semiquaver rhythm and an ascending octave leap. Immediately after, in the second chord, we encounter what appears to be a neighbouring note.

The second chord is conceptually a V7, therefore the F# on Violin I is a non-harmonic note, a retardation resolving in G. However, through the lenses of counterpoint, the F# is consonant, while the G should be considered a neighbouring note.

That is why the consonant non-harmonic F# is described in a parenthesis.

Bars 45-46. Lead 2 starts by doubling Lead 1 a third above on the first half. Notice that all three Violins start with an ascending leap of octave.

In the second half (bar 46), the First Violin is briefly conversing with the Second.

Bars 47-50 introduce a new Accompaniment, one that plays almost identical notes to the Introduction, but uses Suspensions as a variation. It mostly consists of a descending stepwise motion.

Notice that in bar 49, the First Violin enters with an ascending leap of octave. Thus, in this Cycle, there are at least two voices initiating their motive by leaping.

CODA

Bars 51-57

For the last 8, the leap of octave is a very prominent element.

The melodies are almost exclusively consonant and descending.

These last bars function as a decompression, a liquidating of the melodic line to its simpler elements and heading towards the final cadence.

START YOUR FACE TO FACE OR ONLINE PIANO LESSONS WITH US

Visit our Blog and Homepage for more articles like this! And join our Music Analysis courses to deeply understand how to analyze classical music.