Uncategorized

The “Blackhole” in their appreciation: The Arpeggio

Introduction

Piano Arpeggios

What is an arpeggio?

An “Arpeggio” can be seen as a set of notes played in a particular order, in which they create a mesmerising effect as if played by a melodic harp (or as guitar arpeggios)

However, there is an intricate world behind the surface of what we see and perceive when we hear an arpeggio. Many of us pianists and composers have studied in depth the internal components of this melodic pattern.

However, some students and amateurs still might not have explored all the possibilities of playing scales AND arpeggios on piano.

We have been taught piano arpeggios are just a simple pianistic exercise. Yet, some of us, pianists, might not have realized that in many movies, pop songs and even TV openings, arpeggios are used profusely!

The arpeggios are widely used in solo improvisation performance and even by the most well-known jazz pianists.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=saGYnP7I37Q

Whether you’re a pianist, composer or someone who just began to learn to play the piano, this article is directed to you!

Arpeggio

How to create an arpeggio?:

Before we dig deep into the arpeggios’ secrets, we should first unveil the challenges related to delivering them in performance.

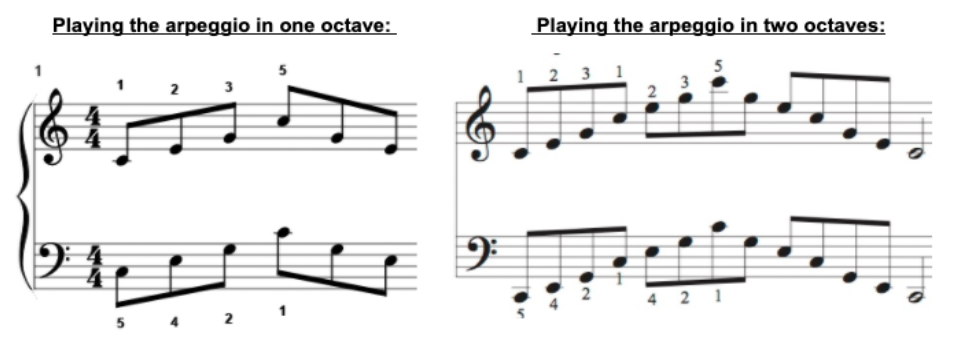

Piano arpeggios are a part of the foundations of learning how to play the piano. They can be played with either hands-separately or hands-together. Our approach to scales and arpeggios is quite similar, technically speaking.

Nevertheless and as opposed to scales -which are organised step-wise-, arpeggios on piano showcase interleaved notes positioned in several combinations of intervals.

In this article, you will encounter:

- Roman numerals used to reference chord structures.

- Arabic numerals used to identify notes in a scale or an arpeggio.

You can find more info about this notation approach at https://www.jazzguitar.be/blog/roman-numerals-analysis-transposition/

Some Types of Arpeggios

Major arpeggios

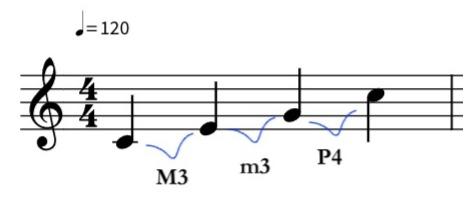

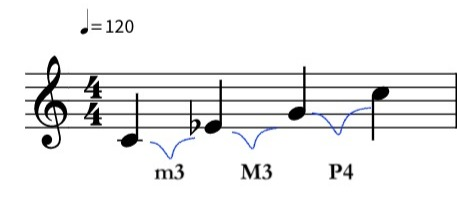

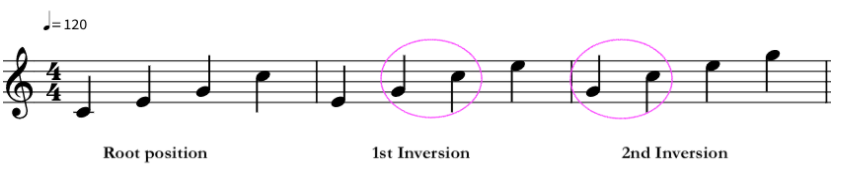

We can build up a four-note-arpeggio starting on the tonic, then staggering a major 3rd (M3), followed by a minor 3rd (m3) and ending on a perfect 4th (P4).

For example, if we take the four-note-version of the C Major arpeggio, we will play C E G notes, and we will end on C again.

In Jazz literature, we would describe this same thing numerically as follows:

1, 3, 5 and 1

These numbers are used in Berklee College of Music to notate the degrees of a scale.

For more information and examples you can visit https://www.berklee.edu/core/glossary.html#terms-arranging_1 and search for some arpeggios PDF on the internet.

Minor Arpeggios

We can build up a minor arpeggio by staggering an m3, an M3 and a P4. This structure applies to all minor arpeggios.

Arpeggios using the 7th chords

As we have mentioned before, all arpeggios are a horizontally deployed and non-simultaneous version of a chord. Ergo, the structure of all arpeggios is based on their analogous chords.

In the case of arpeggios with the 7th, instead of completing them by repeating the tonic after the 5th, we just add more tension and colour by adding the 7th. In the case of C major arpeggios, the M7 degree is B.

Whether you are using a piano learning software or you want to learn piano online, you can have a better picture of its structure as you can see it through your phone or laptop screen. ios are the horizontal expression of chords.

We can build up all different types of 7th-chord-based-arpeggios by modifying two main components of the 7th chord:

- The triad starting from the tonic. This triad can be major, minor, augmented or diminished

- The 7th. The 7th can be major, minor or diminished

Out of all the possible combinations of triads and 7th, there are some that are more popularly used in western music.

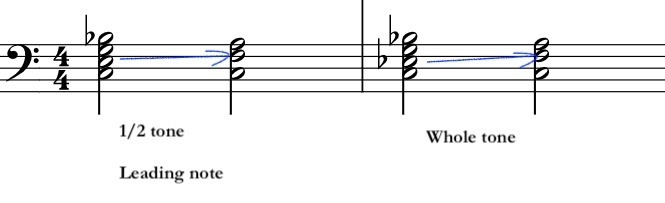

Dominant Seventh Arpeggio

The dominant seventh chord -and, therefore, its “arpeggiated” counterpart- is by far the most popularly used seventh chord in western music.

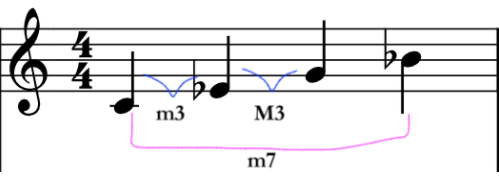

We also have the “Dominant 7th arpeggios”. These ones are typically used to resolve to the tonic. Their structure consists of a major triad and a staggered m7.

In the example above the dominant seventh chord is built of G, B, D and F.

Major Seventh Arpeggio

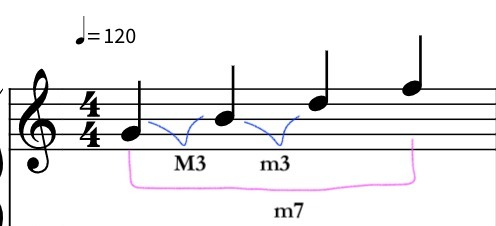

The unique sonority of the major seventh chord bonds it with jazz music, as it is used the most in Jazz standards.

The notes used to build up a Major 7th in the example above, are C, E, G and B. All together they build up a major triad followed by an M7.

A very mellow sound characterises the major 7th arpeggio. The latter makes it especially useful to accompany ballads as well.

Minor Seventh Arpeggio

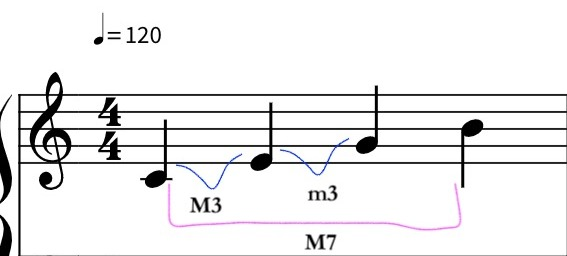

Another combination of triad and 7th is named “minor 7th arpeggio”. In this case, both the triad and the 7th are minor.

The notes in the example above are C Eb G and Bb.

It somehow projects a “relaxed-tensed” atmosphere, certainly less shiny than the Major 7th.

Mostly because the minor third pushes far less towards a resolution on the tonic than the major third of the major 7th chord.

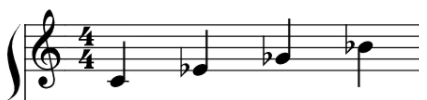

Fully Diminished or diminished 7th arpeggio

The “Fully Diminished or diminished 7th arpeggio” is the most used of all the diminished 7th arpeggios. Amongst them, the diminished major seventh or the dominant-seventh-flat-five deserve special mentioning.

The diminished 7th chord is a seventh chord structured starting from a root note, followed by a minor 3rd, a diminished 5th and ending on a diminished 7th. Therefore it is built up from a diminished-triad and a diminished 7th.

In the example above the diminished 7th consists of the notes C, Eb, Gb and Bbb. Notice the seventh degree of the arpeggio, the B, has two flats -it is a “double flat”. Hence the interval of the 7th is diminished rather than minor.

Half Diminished 7th arpeggio

Most of the jazz musicians consider the half-diminished 7th as the “Minor Seventh – Flat Five” chord/arpeggio.

Harmonically, it is typically used as part of the musical lick to resolve to the tonic colourfully.

The notes in the example above are C, Eb, Gb and Bb. Notice here that the seventh degree of the arpeggio, the B, has only one flat, hence the 7th is minor.

For more information and examples visit https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Half-diminished_seventh_chord

All of this information looks like a snack!

Uses of Arpeggios

Arpeggios can be used as dexterity exercises or a resorce when they are a part of a classical piece when you play the piano.

Arpeggios can be expressed in a score using different note durations: as triplets, crochets, semiquavers…

Also, arpeggios are mainly used as accompaniment resource. They are rich in colour and texture and they can reinforce the key signature or the time signature of a piece.

The most common one is the “Arpeggiated Chord” which is notated on the score with a wiggly line starting from the bottom of the chord till the last note of it. Like the example below:

Another widespread use of it is through the “Alberti Bass”, an accompaniment pattern which we can relate to the shape of an arpeggio. The main difference being the pivot point.

An Alberti bass will structure the three notes of a major triad so every four notes -for example- we hear a top or bottom pivot note twice while we hear the remaining two only once. See example above.

Popular examples of Alberti Bass in Pop songs

We can identify Alberti bass and arpeggios in pop songs too!

One of them is “Someone Like You” by Adele. In this work, she makes use of the same pattern for her introductory piece.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hLQl3WQQoQ0

Beyoncés famous hit, “Halo” also works similarly.

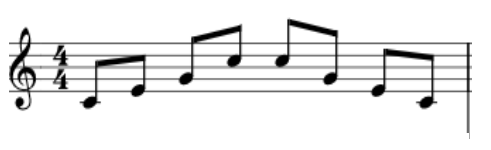

Arpeggios Vs. Broken Chords

Even though a broken chord sounds very similar to an arpeggio that doesn’t mean they are both the same thing.

Many pianists get confused with these two terms, mainly because both might share common fingerings.

A broken chord is the arpeggio pattern broken into segments in which the pattern of a single arpeggio strand gets repeated.

The latter looks like a “stretch” of it, as shown below:

Piano arpeggios technique

The “arpeggio technique” is not an easy one, and having to perform them on a piece isn’t a “piece” of cake!

A very wise composer and piano pedagogue, named Vicente Scaramuzza has studied hand movement with a big deal of in-depth. Based on his realisations, we will play an arpeggio starting by approaching the keyboard with a small expression of the active phase of the forearm movement. We will then continue deploying finger movement.

You can find all possible arpeggio fingerings at www.wkmt.co.uk/scales-and-arpeggio

When we exercise the arpeggios technique using finger movement, it is fundamental that we exercise “articulation”. The latter means we have to try and flex up and down the fingers, so they reach the maximum “relaxed” height.

Below a recording by Juan Jose Rezzuto of Chopin Op.10 No 1. In this recording, Rezzuto exercises this approach to obtain maximum clarity and control over all main passages.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z5LkO2sjGFo&t=27s

It is essential to keep our wrists flexible but firm; think of it as a camera stabiliser.

Below, a picture of how a hand might look when exercising arpeggios in slow motion.

One way of practicing to perform arpeggios correctly is to play them stressing one note every 2, then every 3 and then every four.

https://video.wixstatic.com/video/255d68_8096119982e64f01ae60c8b60d872344/480p/mp4/file.mp4

You can play the arpeggios staccato or legato.

You may practice the arpeggios following these other rhythm patterns as well.

Arpeggios in Orchestration

The Arpeggio pattern is applied to all instruments and ensembles. We can see it in music written for string instruments or woodwinds, for example. However, when applied to the orchestra things change drastically…

Using an ensemble to deploy an arpeggio can offer us, composers, infinite possibilities of instrumental combinations. The latter allows us to achieve the most stunning sound effects.

To orchestrate an arpeggio successfully, the composer should know how each family of instruments behave in the context of the orchestra, their registers, their compared intensity levels and their timbres.

An arpeggio can be deployed in different ways for each instrument family. The latter translates into a pallet of rich and colourful sounds we all perceive from the orchestra.

Arpeggios in String Section

The string section will use each of its instruments to deploy the arpeggio within their note range.

The violas will play the middle range notes, the violins play the higher range and middle notes, and the cellos play the low register notes with the double-basses. Each instrument has its unique resonance and reverberation.

The score can project a “cascade” of notes based on an arpeggio pattern. We can achieve this “cascade” effect by orchestrating a sequence of notes in a particular manner. Basically, each instrument plays a certain assigned arpeggiated fragment.

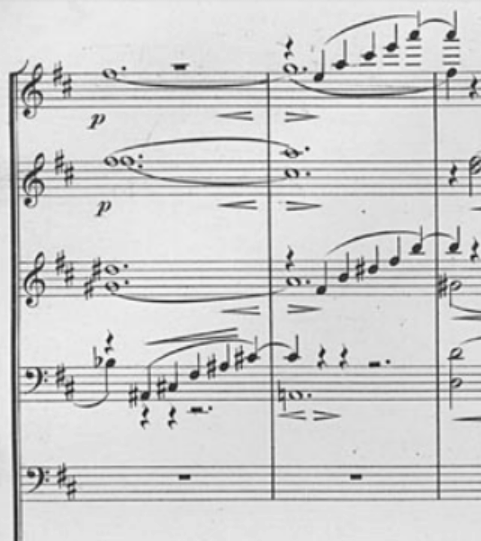

See the example below.

The orchestral design above delivers an acoustically organised version of the arpeggio to the listener, which is both elegant and effective.

The bass instruments will sometimes get to play the least exciting section; however, their part plays a fundamental role in supporting the whole harmony and structure of the arpeggio.

Arpeggios in Wind and Brass

With the Woodwinds and Brass, the situation is similar.

Instruments collaborate and can even share a range when deploying the arpeggio notes assigned.

The flutes play the higher notes, the oboes play both the high and middle range notes, and finally, the horns and bassoons play the low register notes.

Take a look at the example below extracted from Brahms Symphony No. 3, Mov. I.

In this example above, we can see how Brahms works on arpeggiating the F# and A major chords.

His instruments of choice are the bassoon, the clarinet and the flute. We can see how he firstly assigns F# major chord to the bassoon so it spreads it through almost two octaves; subsequently, he will land on the top register by doubling A major arpeggio with the clarinet and the flute. We can arguably say he is trying to produce an environmental filler-harmony effect by travelling comprehensively through the registers of the woodwind family.

The effect of this orchestration complements and embellishes the melodic line and the strong harmonic support provided eminently by the string section with the collaboration of the brass.

“Registry-wise”, on the first bar we can see how the arpeggio deploys the first inversion of the F# major chord that leads to A major in the second measure. The pattern begins with A# and opens up and climbs towards a crowning “high” A natural on the flute on measure two.

Other Uses

Arpeggios can also be orchestrated in their “broken-chord” version. This allows the object to take more “time-space” within a certain fragment. Basically, this strategy lengthens the passage postponing a goal on a top high note for example.

An arpeggio can also be seen in other formats and events, like the piano solos in jazz as well. Since when someone improvises, the basic rule is to “musically speak” within the key given. What the jazz performer does to stay in the key is entirely up to him or her.

Conclusion:

As we have explored, the arpeggio isn’t just an exercise. Therefore, it is very commonly used to embellish music with the derived patterns coming from its structure. The level of complexity applied to the musical writing when implementing arpeggios will vary depending on whether you are using an orchestra, a chamber ensemble or the piano solo.

Composers have been using arpeggios for centuries. That doesn’t prevent contemporary music producers from still finding a good use for arpeggios in pop songs.

The Arpeggio honours its name by reflecting the etymological origin of the word “Arpeggio”, which comes from “Arpeggiare”, in the impression it gives to us when we listen to its evenly spaced skipping notes.

Now it is your turn to experiment!

Practice and, most of all, have fun while discovering all the possible patterns, combinations and orchestrations you can produce inspired in the shape of this fabulous idiom of music;

the most commonly known “Arpeggio”!

This article was written and designed by Juan Rezzuto and Ana Ortiz