Uncategorized

The Liszt Tradition and its Influence on Modern Piano Technique

The world of keyboard instruments has evolved greatly over the centuries. We still remember the harpsichord, a keyboard instrument of plucked strings which was very popular in the Baroque period, as well as the clavichord, an instrument which most resembles the mechanism of what will become the pianoforte. With the arrival of the 18th century, and the invention of the pianoforte in 1700, the repertoire of the keyboard took on a huge force with respect to its expression in music. Seeing as it wasn’t possible to create graded dynamics on the harpsichord, an effect which is very clear on instruments such as the voice or the violin, with the arrival of this new invention, the pianoforte, music took on a superior level in aspects such as articulation and expression.

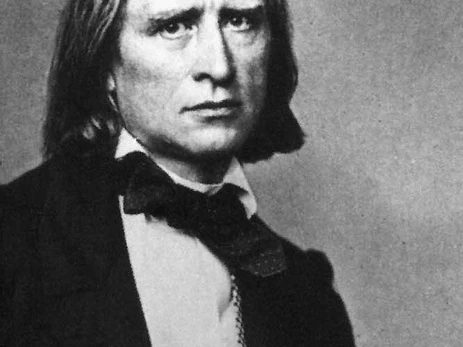

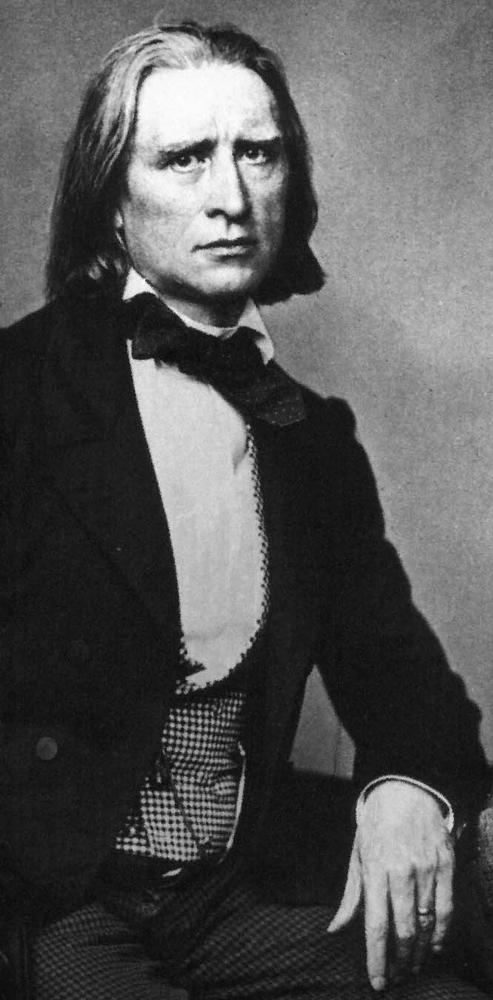

A composer and pianist regarded as a founder of modern pianism or modern classical music. Liszt was seen as the, or one of, the greatest pianists of his or any generation. What is more so overlooked is his development and how he had reached these innovations and changes from his own roots of Beethoven and Czerny, then the developments that had spread throughout Europe. The technique developed hand in hand with the developments of the piano itself in the 19th century.

An often-told story of a turning point came from Paganini’s concerts. Liszt had begun to develop a new and continuously evolving technique. However, it was also known that Liszt didn’t directly instruct his students from a technical point of view. The main focus was on the interpretation.

Liszt had reportedly worked on the pedagogy of piano for twelve years but then abandoned it and focused on composition, performance and instructing his students.

Much of Liszt piano teachings and demonstrations were spread by word of mouth. As a result, they may have been altered or developed in slightly- or widely- different ways. It’s also important to note that students were taught at different times when Liszt’s own technique (along with pianists in general) was still changing and developing as the instrument was developing: so we may get many different and sometimes contradicting accounts from students over the years.

Ultimately they had shaped the branches of many piano traditions- especially the Russian tradition, the developments of piano music in Germany passed through Europe- and, quite possibly, the Scaramuzza technique!

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:F._Liszt_1858.jpg

The origins of Liszt’s technique

A pianist fingers

It had been trained with the Viennese school. His teacher Czerny instructed Liszt to use fingers and wrist only. Yet the knuckles, wrist and forearm were to follow a straight line without slanting. Plus the stool had to be proportioned so the ends of the elbows would be an inch above the keys. This method of playing was suited to keys shallower and lighter.

Meanwhile, the English style of pianism preferred the full tone of the instrument. This became influential in Paris where a more singing tone had developed, whereas the Classical method had been more a detached high finger action.

For Liszt, however, this classical method would soon cause limits in his playing, and he started to move away from this method gradually. In performing to his close friends like Rossini, he had complained of getting pain in the wrists. He had explained in letters to his mistress Marie d’Agoult. Liszt called himself ‘an amateur’ with ‘strong wrists.’

What had followed became Liszt’s intuitive way of finding solutions to the technical problems he set himself. The technique slowly started to change.

Some pictures of Liszt depicted him sitting even higher above the keys with his arms slanting downwards (possibly to provide the extra force behind the wrists and fingers). Other changes, such as a more flexible hand that kept no fixed shape became apparent to students.

This might not be evidence of the arm weight method (which came later in the 19th century), but there were many conflicting accounts as to whether Liszt started to use arm weight directly- or had stuck with only wrist and fingers.

In the lesson diaries of Madame Auguste Bossier dated between 1831-2. Her daughter Valerie, who took lessons with Liszt, was always insisted on to rely on the fingers and wrist. These were particularly important for tone production– but without interference from the arm or shoulder. It also noted his fingers kept flexible with no fixed position.

Although it is said, the encounter of Paganini in 1832 had caused him to start restructuring this technique. Accounts show not much evidence of this. In his letters to the Bossier a year before, he had already discovered his inability to successfully play trills, octaves and chords and so set about changing his approach to the touch and create more flexibility in his wrists.

Liszt may have been influenced by Paganini, yet his habits of practising exercises (in thirds, sixths, octaves, tremolos, repeated notes, cadenzas etc.) was exactly the same as before. He always stressed to his students the needs to flex and relax the fingers in all directions. All these exercises and finally ‘everything that one is capable of doing’.

There is plenty of evidence to say that although Paganini may have inspired Liszt to ‘re-learn piano technique’, this long-held myth is somewhat true- but only to some extent as Liszt’s inspiration here seems more of a compositional one rather than a revolutionary technical one.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Niccolo-Paganini.jpeg

He still kept the finger-wrist training from Czerny (with some modifications to hand shape, supple wrist and arm angle established before). Plus the centre focus of his practising was still the type of technical exercises you would expect to find by Czerny-or Hanon– such as thirds, octaves, trills etc.

While teaching in Weimar, Germany, one particular student who studied with Liszt from 1873 was Amy Fay. Fay studied previously with other pianists Tausig, Depp and Kullack. Having the benefit of comparison, Fay notes down in her diary of Liszt’s teachings.

What described matches the Bossier diaries forty years previous of a similar finger-wrist technique. His playing included keeping fingers closer to the keyboard than what was conventional; with fingers slanting over the keys. By making too much hand movement, Liszt had remarked to her: ‘hand still, Fräulein. Don’t make omelette.‘

Other students account that Liszt was solely focused on the ‘spiritual and intellectual element of the music’ and guiding them ‘towards a freer position of the hand‘ and ‘elasticity of the wrist‘. Also to maintain the practice of large scale studies in passage work and octaves and to play difficult passages in all keys.

As evidenced here, Liszt didn’t give the regime of dictating technique as he said: ‘wash the dirty linen at home‘- his students were already of an advanced level.

He encouraged a freer approach without over influence on the student: so the student can find their own artistic personality and technical solutions such as fingerings.

Liszt would very rarely demonstrate or play to his students (only to recommend fingerings). Some students had tried to catch a glimpse of Liszt playing. At one point Irish dramatist Edward Martyn visited Villa d’Este outside Rome- where Liszt was staying. After finding out when he would practice, he sneaked to the window of the residence. Where he hoped to hear playing of pieces- all he found was Liszt practicing scales for probably at least an hour!

Although Liszt keeps a variant of the same Viennese method from Czerny, there are many accounts (such as Moscheles) of his playing in concert where his arms are ‘flung in the air’ in a dramatic way. This may have contradicted his teachings and suggested arm-weight technique but became more of a caricature of Liszt.

During the first half of 1800

There wasn’t a great deal of wide knowledge into using the arm-weight technique. Only from the end of the century did it appear more frequently.

Pianist William Mason had studied with Dreyschock and Liszt. He didn’t recall anything said about the arm weight. However, they did place importance on the wrist and ‘sought for a more orchestral manner of playing.’

In an article by Ernst Pauer in the 1889 Grove dictionary of music he describes this ‘orchestral’ playing:

The rise of virtuosic playing from the 1830s had ‘increased force and rapidity demanded an alteration of the movement of the arm, hand and a swinging movement of the hand’ This ‘playing from the wrist, or a nervous force from a stiff elbow’ had created a more harsh, heavy-hitting from of playing that was known as ‘thumping’. Pauer had linked this form of playing to Thalberg, Dreyschock, Handselt and Liszt.

The orchestral capacity of playing is clearly shown in Liszt’s transcriptions of Schubert’s songs, Operas and Beethoven’s famous Symphonies.

From the 1900s

Contemporary piano music

There came a spreading theory that Liszt had founded the arm weight technique. Accounts by Breithaupt, (a leading advocate of the arm weight school), Harold Schonberg’s book ‘The Great Pianists‘ and Bertrand Ott’s ‘Lisztian Keyboard Energy‘. They state about Liszt bring the first aware of an arm weight technique with loose shoulders and a high angle of the arms and fingers.

Although it couldn’t have been a relaxed weight as in Scaramuzza (the elbow is positioned below the keys facing down rather than held in an upward angle).

What was developed in the wrist technique and passed on from Liszt has had many followers of Liszt accused of ‘thumping’. The adding of the whole arm, wrist and hand technique at the time were linked to pianist-teachers like Deppe and Mason.

The development of the arm weight however, was appearing in many countries simultaneously throughout the late 1800s. Even the American pianist-composer Godowsky claimed to have discovered it in 1891.

By this time, it is possible that arm weight came as a reaction to the new developing pianos with stronger key action and resonance. They were championed by Liszt with the grand piano open at a right angle to the audience. However, such ‘thumping’ of the wrist came at a loss of a more rounded smoother sound.

It wasn’t until the 1920s that Scaramuzza had begun to look into solutions for the tension of arm weight; so he explored this to the very core. He studied the arm anatomy and developed a more relaxed use of the arm weight. This would support a more rounded tone- plus supporting louder dynamics that wouldn’t be potentially damaging to the arm.

The start of Liszt’s technique may have been Czerny’s Viennese style, but following pianists and traditions have started to combine Liszt’s approach of loose, elastic wrists with other movements of the arm currently in development. The Russian school is one particular example.

While in Russia

The principal technique had come from Irish pianist Field (who was trained by Hummel’s classical method).

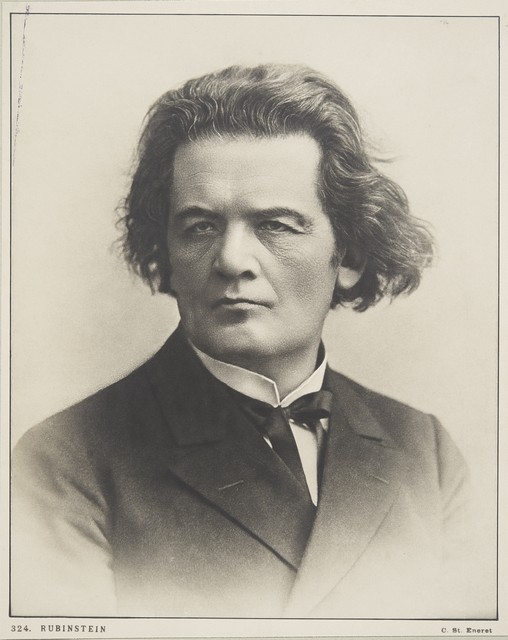

Originally there was a clash between the Russian conservatories: The refined Classical finger work of Field and the disapproval of Liszt’s style. However, this new Liszt tradition had greatly influenced pianists such as Anton Rubinstein and Balakirev.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Anton-Rubinstein-1890s.jpg

An important point here is the Hummel’s method actually also came from the Viennese school- just as Liszt’s was. However, there was now a clash-which strongly suggests by this time: Liszt’s current method taken into the Russian school was now much different from these Viennese Classical roots.

The Rubinstein brothers Nicolay and Anton had founded the Moscow and St. Petersburg conservatories respectively.

Balakirev was one of ‘The Five’: amateur pianists who focused on composing and rivaled the conservatory approach. Islamey was Balakirev’s largest influenced work, thanks to Liszt.

The influence also reached more traditional conservatory based composers such as Tchaikovsky with his first piano concerto. Eventually, they came to adopt the newer playing style of arm weight, the flexible wrist and a mobile body. This had an impact on overall playing, such as the sound and phrasing to carry over in a large hall. This new approach was completely different from where in Russia piano playing was more a domestic activity.

Rubinstein had commented that Liszt laid deeper roots in Russia than he did anywhere else.

Liszt had completely reshaped the Moscow conservatory from the teaching staff to the technical approach and new repertoire. Meanwhile, Liszt allowed his own students the new repertoire from composers such as Balakirev.

Liszt’s traditional teachings were so profoundly influential that they filtered through composers such as Tchaikovsky, Busoni- who originally developed the Liszt Tradition at Moscow returning to Italy. Even an ‘anti-Lisztian’ Safonov (teacher of Scriabin). Liszt’s pupil Silotti- who was the teacher of Rachmaninov. Later composer Prokofiev and all the way to professors today.

Back in Germany

Two particular close students of Liszt: Stavenhagen and Kellermann. Both were professors at the Royal Academy of Music in Munich. Stavenhagen had succeeded Liszt at Weimar and Kellermann before was secretary to Wagner. Liszt commenting on Kellermann ‘if you want to know how to perform my works… ask Kellermann- he understands me’.

From direct accounts of these pianists, plus their students, we have more accurate details of the overall technique. They confirm Liszt’s primary use of the wrist- plus rotation similar to the Scaramuzza definition. One important starting exercise was Klopfübung. This involved exercising each finger in a drumming-like manner. The bulk of the work involves scales of all keys and intervals.

Conclusion

This goes to show that for Liszt’s technique, the Classical method from Czerny was always central to Liszt’s playing. Plus the addition of other techniques developed at the time- including elements borrowed from Thalberg and Dreyschock.

Although Liszt may have been influenced by Paganini to use difficult and innovated techniques in their playing, the technical basis of both players actually comes from an old epoch.

For Paganini, it was recently supposed that he played using a very old Baroque style of holding the violin with his hand while only using the wrist to change positions. (The wrist becoming a common element of both players).

None the less because of changing styles and extra demands- such as heavier keys of the piano: both had to alter and adapt their technique on some level to meet these new demands.

We know plenty about Liszt’s compositions and make assumptions on the playing, but it’s really Liszt’s personal messages and teachings that run the risk of becoming lost.

Finally, some Liszt piano concertos for you to enjoy!

Liszt Piano Concerto No. 1 by Martha Argerich

Author: Anthony Elward

Learn more with WKMT London!