music production, Music Theory Resoucers, Uncategorized

Musical Composition – Four options of continuation

Music is essentially movement: from the first vibration of a single string to the massive sound of an orchestra playing “tutti”. Any sound that follows may reduce, intensify or confirm the embryonic sense of movement, thus creating an overall shape which appeals to the memory of the listener whenever the piece moves forward. This brings us back to the initial premise: how to develop this movement to create the shape we want to achieve in our compositions?

This is a question that all composition students ask, and even musicians with lots of experience in the field do ponder.

In this article, I intend to shed some light on the matter and help to structure in every composer’s mind, regardless of the level, style and background, the options available to assist in this process.

All options can be reduced in four basic ways of continuation:

1.- RECURRENCE

This is the first and the most basic way to continue a motive or phrase. It could be an exact repetition of either a motive, sub phrase or phrase. The dimensions of repetition can vary in small, medium or large. In large dimensions, the typical example is the return to the same section after a change. The most common case is in the ternary form in which the A section comes back after the B section, or in a rondo form when the main section, also called the “Theme” or the “Refrain”, which comes back after the initial statement and it keeps returning, hence the name “Rondeau” which comes from French and means “Round”.

The most famous example comes from the hand of L. V. Beethoven with “Fur Elise” in which the well-known refrain keeps returning after contrasting sections.

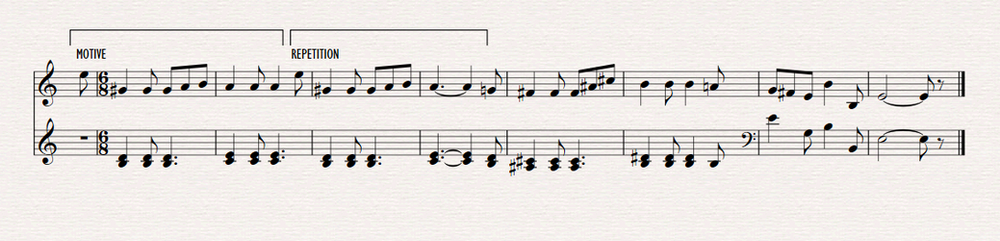

The next example is focused in a small dimension, in the beginning of this piece “Sicilienne” from the Album for the young of Robert Schumann, his first decision is to repeat the same motive of bars 1 and 2 in bars 3 and 4 to then develop it by transposing to another chord (a secondary chord to lead to the dominant).

2.- DEVELOPMENT

Or also called “Interrelationship” Comprises variation and mutation. This is a more complex for of continuation and it is expressed in bars 3 and 4 of the “Sentences”. This term was coined by Arnold Schonberg, a composer and German theorist in which he explains the most common openings for Sonata forms or other large forms.

The continuation through development is the most effective resource for a composer to give variation upon a motive but still keeping the main features of it. In the following example of the first movement of Ludwig Van Beethoven Sonata Op. 2 No. 1 in F minor, we can observe that in bars 1 and 2 the motive is expressed on the Tonic level and immediately after in bars 3 and 4 the same melodic contour is adapted to the Dominant level. Please notice that the mutation resides in the fact that the motive is not transposed to the dominant, but adapted to it: The notes of the chord of F minor (the tonic chord in bars 1 and 2) is then adapted to the Dominant seventh chord of the main key, C7. Also, if we take into account the first bar the notes of the arpeggiato chord displayed are the 5th (C), the root (F), the 3rd (Ab), then 5th again, root, finishing the melodic contour in the first climactic note, Ab, which is a third of the chord of F minor again. This is not followed to the letter in bars 3-4, in which we can clearly see that the notes of the C7 are unfolded in the following order: root (C), 5th (G), Root again (C), 3rd (E), 5th (G) and lastly, the seventh, B flat.

3.- RESPONSE

Or also called “Interdependence” This option of continuation does not add new elements as the Development but works as a way of complement the first statement. The response needs the first part to exist, hence the name “interdependence”. Some examples in the four contributing elements:

Sound: Forte Vs. Piano

Harmony: Tonic Vs. Dominant

Melody: Rising Vs. falling, stepwise Vs. skips or leaps.

Rhythm: Stability Vs. activity or directional motion, the balance between modules or for example, 4 bars against 4 bars, etc.

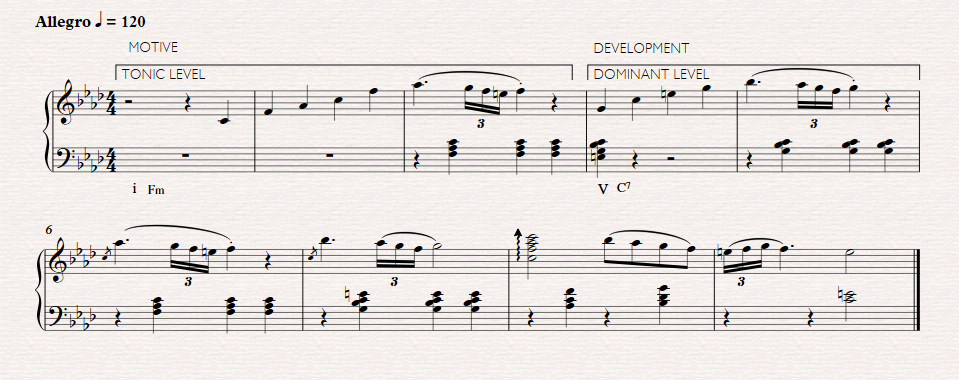

Here we can see in one of Johann Sebastian Bach Masterpieces, The two-voice invention in C Major BWV 772. Bars 16 – 19:

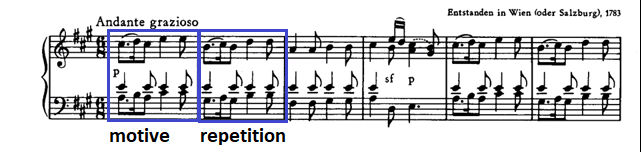

Another example in a small dimension can be found at the beginning of the renowned Sonata in A Major, K. 331 of W. A. Mozart, in which the first choice for the composer is to response the motive in the tonic (bar 1 ) immediately in bar 2 on the dominant level:

4.- CONTRAST

This last option is the least used as it can be quite “risky” if not done properly. The contrast is basically to oppose the elements presented but keeping the motive structurally coherent. A composer may vary the key, or mode (for example to turn a minor motive into a Major mode), or changing the time signature from a simple to a compound meter.

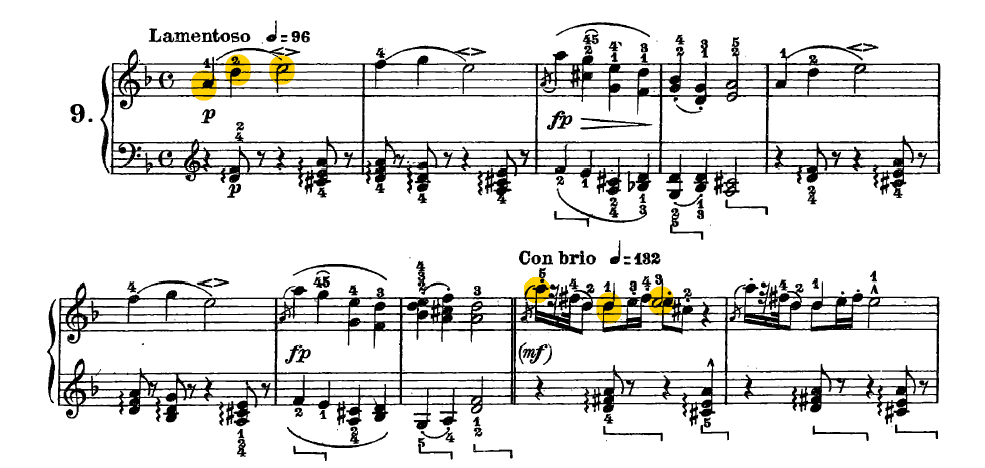

The number of elements has to be enough to feel that something drastic has changed but always keeping in mind that the listener should always have conscious or unconsciously, a ground to step in. Here is an example of Schumann taken from the book “Album for the Young, Op. 68 No. 9” the song is called “Popular Song” in which we see the first section “A” where the main motive is presented under a slow tempo (lamentoso), a minor mode (D minor to be more precise), a rising melody in crotchets (or quarter notes) and a homophonic chordal accompaniment in an arpeggiated form. The “B” section starting on bar 9 has many aspects which can be considered in opposition as the first: a parallel major mode (D Major), shorter values which also provides a more ornamented melody and a much faster tempo (con brio).

Apparently, everything is in contrast to the first statement, but as composers and analysts, we should go further from what the naked eye can perceive. Notice that the first notes, A, D and E are still in the skeleton of the second section, in this example coloured in yellow. This openly demonstrates that the composer should always keep some structural elements intact to keep a safe ground to the listener, under an apparent change of path. Also, the texture of the accompaniment remained intact.

Here we can find another example of contrasting continuation in another Schumann’s song “The Italian Sailors” from the same “Album for the Young, Op. 68”:

CONCLUSION

These for options of continuation should be taken in every dimension of a composition, as the way of continuing can be combined in every dimension. We have a case at the beginning of Mozart’s Sonata in A Major, K. 331 seen in the RESPONSE section.

The first bar is continued through a response, but then in bars 3 and 4, we have a DEVELOPMENT way of continuing the piece, while in bars 5 and 6 Mozart uses RECURRENCE and then finishes with a cadence similar to de previous development. This clearly shows us that composers are constantly using this tool on every step of the way.