Haydn Sonatas, Uncategorized

Sonata in C Major Hob XVI.1 – First Movement – Haydn

The Sonata in C major is the first composed by Joseph Haydn, one of the leading composers contributing to the development of the Sonata Form. His Sonatas influenced musical history significantly.

The analysis of such works can be beneficial for performers, composers and theorists alike.

OBSERVATION

The Haydn Piano Sonata in C major is a piece is in three Movements; ‘Allegro’, ‘Andante’ ‘Minuet-Trio’. The three-movement Sonata was prevalent in that period, before the adaptation of the four-movement in the Romantic period.

The layout of the Movements in the Haydn Piano Sonata in C major is very standard. All the composers have unanimously used the ‘Allegro’ to begin the Sonata. The Second Movement is usually slow, as in this piece, an ‘Andante’, which means “at a walking speed”. The ‘Menuet-Trio’ is a usual finale for Haydn as seen in his next Sonatas (e.g. HOB XVI: 2, 3, 4, 11 and others)

All three Movements are in C major. A shared tonic key can be traced from the Baroque Suite, which was customary to have all the Movements in the same key.

During the Classical period, this tendency changed slowly towards different keys through the movements in a Sonata. This tendency can reveal how Haydn was still composing upon the Baroque style.

However, in his later works, a neighbouring key is preferred for the middle Movement (e.g. HOB XVI: 34, 50, 52). This practice became the custom for the Sonata, by the end of the century.

ALLEGRO – 1st Movement

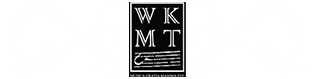

Looking closer to this Sonata in C major by Haydn, precisely in the ‘Allegro’, we can identify each section. The opening theme consists of a series of broken chords, a strongly rhythmical theme, rather than melodic.

The characteristic features of the theme help us locate it again, indicating the beginning of the Elaboration and the Recapitulation (bars 18 and 30).

The total bars of the sections are 17, 12 and 21, respectively. Since the Middle Section of a Sonata is seldom more extended than the First, and the Third occasionally adds material, this ratio is reasonable to occur.

In the Exposition, from bar 1 to 17, we can distinguish the Primary and the Subordinate theme (noted ‘A’ and ‘B’ in bars 1-5 and 8-11 respectively). The first appears in the tonic and the second in the dominant regions.

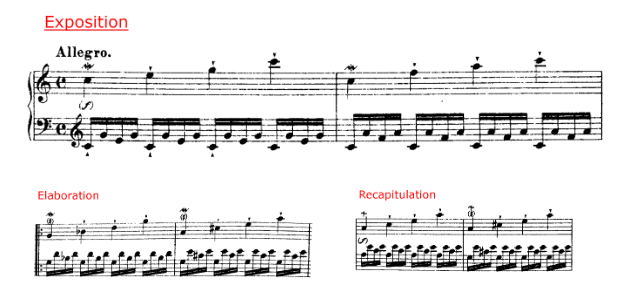

Between them, there is a brief transitional material leading to a cadential figure (bars 6-7).

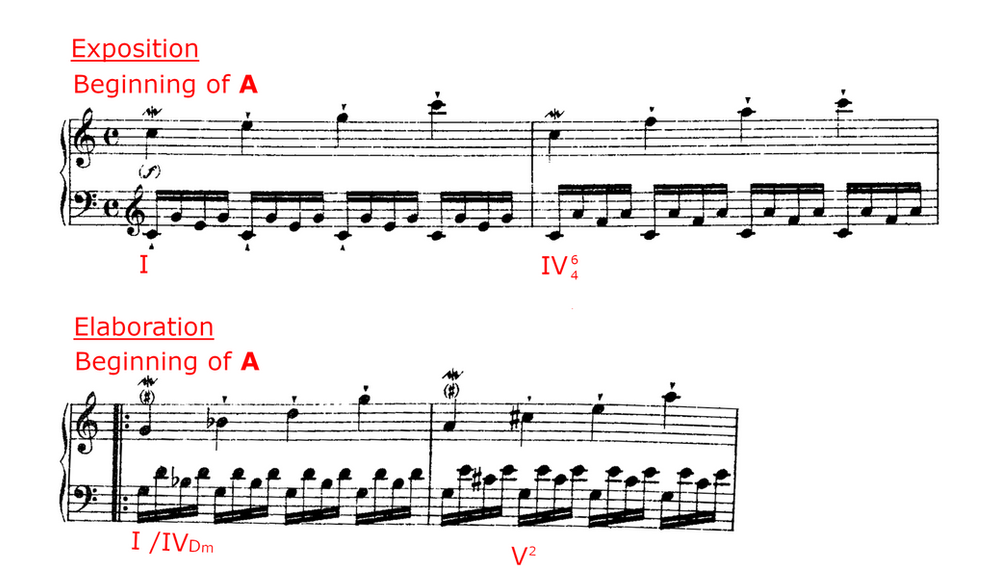

Going back to the beginning, we can examine how the Primary Theme unfolds. The motive appearing in bars 1-3 is a broken chord on the tonic and its variation on the subdominant. A consistent articulation is emphasizing the first beat with the use of a mordent. The IV6/4 is a prolongation of the tonic, bringing harmonic stability, while the Alberti Bass provides textural consistency.

After this smooth presentation, an acceleration in the Harmonic Rhythm occurs with the use of the tonic-dominant relation and a melodic condensation of the original theme. The acceleration is extended with the exact repetition in bar 5, which works like an echo (notice the suggested piano in dynamics), closing it thematically, and moving to the Transition.

We can observe that semiquavers, along with the crescendo, are the main feature of the Transition. The directional motion is leading towards the Cadence in bar 7. Moreover, the accompaniment changes to a lighter texture (more linear than the beginning), while we see the first non-harmonic notes and the first chromatic modulation. All these elements will be seen in bars 12-14 (closing section) and 28-29 (Elaboration) when the same effect is desired.

A common connecting component of the two main themes is usually an upbeat dominant chord before the beginning of the Subordinate Theme. In this instance, however, Haydn gives a solid cadential ending on the new key, G Major. Not only that, but he also provides a full beat of rest in both hands, separating the two themes.

The Second Theme differs from the First in many ways, but Haydn also offers the necessary connections. The most important similarity, which binds the whole Haydn Sonata in C major together, is the Melody. Both themes, as well as the Transition, are based on a broken chord.

However, the dense and active rhythm of the Subordinate Theme, made of anacrustic material and quick but consistent changes of legato and staccato articulation, give the new theme a distinct sound. The Alberti Bass, on the other hand, unites the piece providing a level of regularity to the Surface Rhythm on the left hand. Similarly to the First Theme, the Second Theme ends with a soft, repeated passage, acting like an echo (bars 8-9, 10-11).

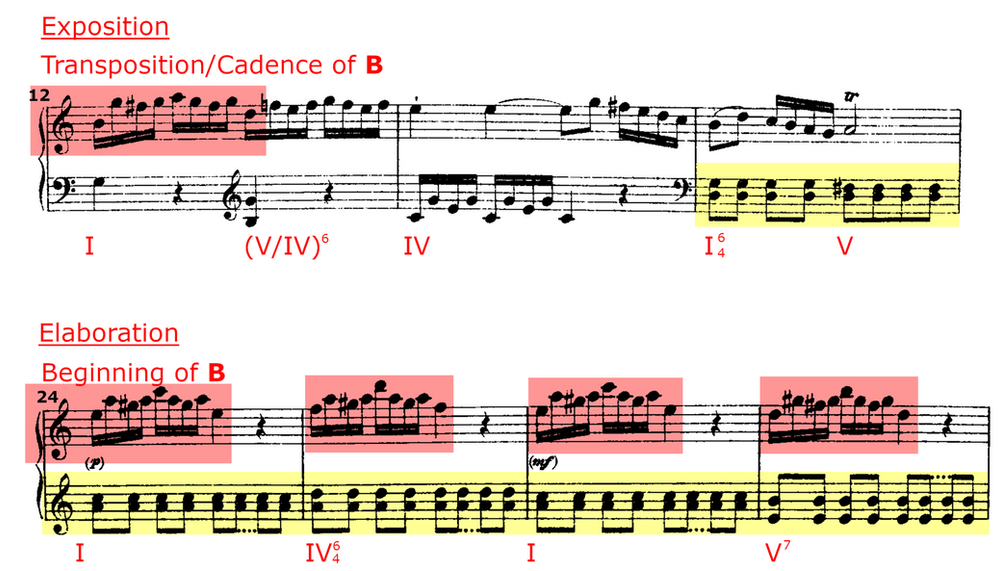

In the Transition that follows in bars 12-14, Haydn uses similar elements to the previous one in bars 6-7. There is a rapid Surface Rhythm on the right hand, a crescendo and a lighter accompaniment, this time provided from rests and then the staccato-legato chords. Additionally, the non-harmonic notes help to produce a directional feeling.

Everything is leading us to the cadential I6/4, V (bar 14) and then an additional closing section (Codetta).

In the Codetta (bar 15-17), even though the Harmonic Rhythm is at its fastest state, the whole section could be interpreted as a prolongation of the dominant chord.

This Haydns’ Sonata in C major has an observable consistency on the repetitions. Both themes, ‘A’ and ‘B’, end with a repetition (bars 5 and 10-11). Now we see that the conclusion of the section, the Codetta, is composed of a repeated motive which is expected to be played softer, as in the similar previous passages.

The elements used in the Codetta are what Schoenberg calls a ‘melodic residue’ (Fundamentals of Musical Composition, page 58). This ‘liquidation’ is also apparent from the tendency to shorter values, and its goal is the final perfect Cadence. The last bar is a more substantial restatement of the previous Cadence.

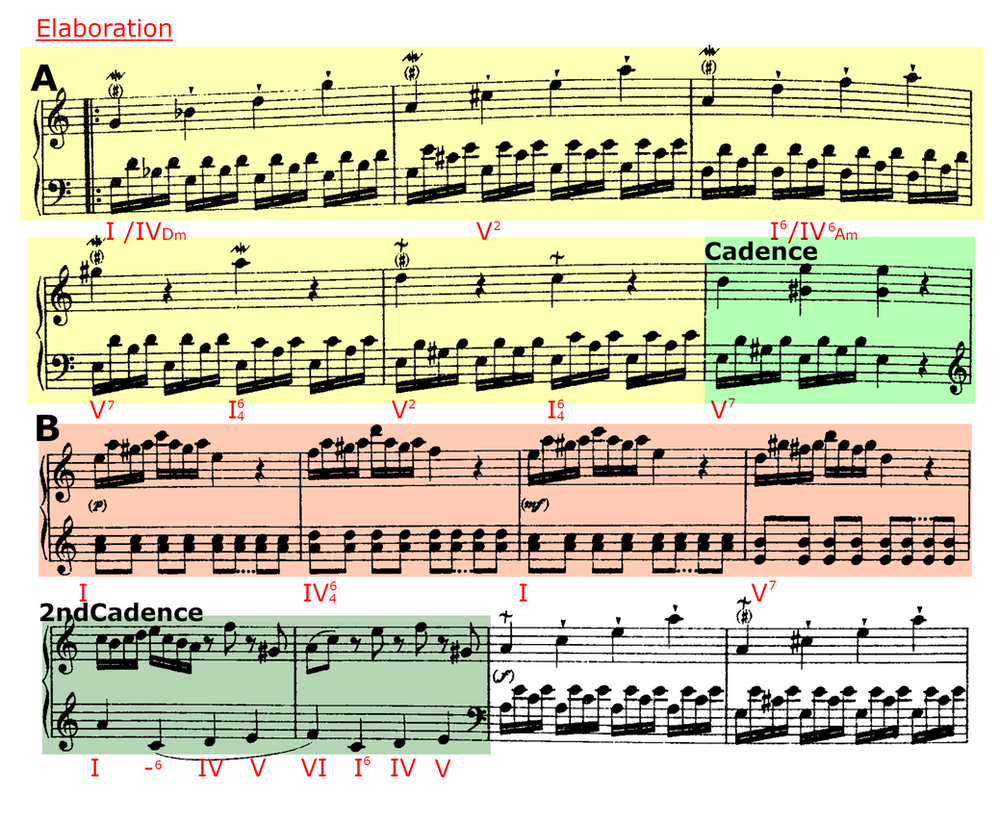

In the Middle Section, we quickly notice that the first half (bars 18-23) closely resembles the theme of the Exposition, functioning as a response to it. The second half (bars 24-29) is a variation of elements in the equivalent part of the Exposition, working as its development, where the composer shows his craft.

Thematically speaking, the ‘A’ of the Elaboration has the same structure as the ‘A’ of the Exposition; three bars of broken chords, two bars of the condensed material and then the Cadence.

The composer chooses to develop the Harmony and modulate to different tonalities, as the form mandates. By re-using the same stable melodic and rhythmic material as before, he can use unstable Harmony without losing balance.

We are introduced to the Elaboration with a shocking G minor (the parallel minor of our last Cadence). G, then, functions as subdominant, followed by the dominant, and then by the tonic of D minor. D, then, functions as subdominant of A minor (parallel of the original key).

Three bars on the dominant chord, prolonged with I6/4, are following (bars 21-23), closing with the same motive as before. Notice that this time we see the variation from the Codetta (bars 15-17).

The ‘B’ makes use of two main motives, which initially had a secondary role. The previously transitional semiquavers are now on the foreground, rephrased once again so that the structural notes outline a triad. Parallelly, the formerly insignificant staccato on the left hand, briefly seen and barely noticed on the second Cadence, has now taken over the accompaniment entirely from the established Alberti Bass.

The Harmony balances out the development in the rhythmic and melodic material. This is achieved, not only by using stable chords in a single tonality (A minor) but by restating the opening Harmony of the Exposition; three bars of I, with a IV6/4 as a prolongation, leading to the dominant. (bars 24-26)

Bars 27-28 are a condensed form of the Exposition’s Codetta (bars 15-16). The chords used are the same as the original (again used as a prolongation of V). Also, both of these sections share the same structural notes.

It is fascinating how the composer manages to compile all the material from the Exposition and re-elaborate it in such an original way, even from this early Sonata. It is clear that, although he chose simple ingredients, he picked them very carefully and made sure not to waste anything.

It is interesting to note here that this ‘B’ unravels in complete contrast to the ‘A’ that preceded. Development of Harmony, balanced out by recurrence of Melody-Rhythm on ‘A’, while the exact opposite happens on ‘B’.

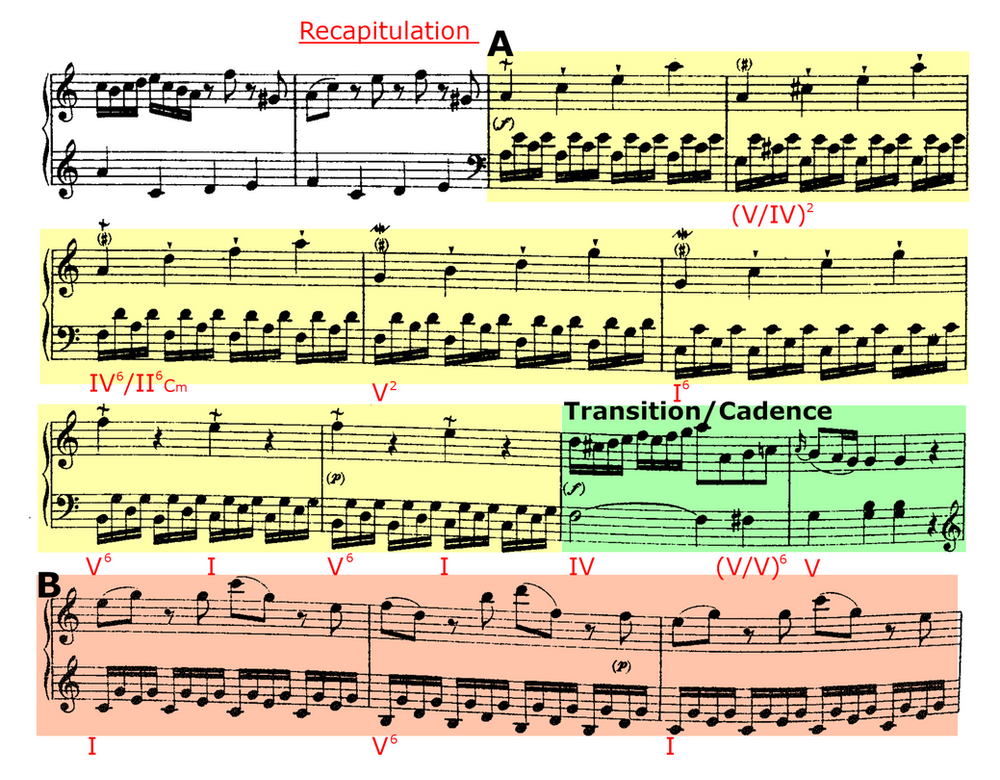

In the Recapitulation, the structure is almost identical to the Exposition. The difference is the elongation of the Primary Theme and the Codetta.

The first addition in bars 29-33 is necessary to return to the home key. Since the last section finished in the parallel minor, the return of the ‘A’ theme merges with a tonal transition. We notice a quick shift from A to D to G to C (opposite to the modulation from earlier), very efficiently done through the circle of fifths.

The chord substitution on the original motive may appear as a surprise since we would expect to enter in the tonic. And yet, we can assume that, in this early Sonata, the composer chose not to modulate back and sacrifice the single tonality, which allowed him to develop the motives and show his craft.

After this gentle return to the original tonality, everything is restated, as in the beginning. ‘A’ finishes precisely like before, only now G functions like an upbeat chord, keeping C as the tonic of the ‘B’ theme.

Finally, the extension bars of the V are now doubled, played an octave lower and forte, re-embracing the closing section, giving the Cadence greater importance towards a grand finale.

Stay tuned for our second and third movements analysis of this beautiful Haydn Sonata.

Learn music Analysis with WKMT Teachers now! Your trial lesson here.