Music Theory Resoucers, Uncategorized

The Period – Main Themes – Sonata Analysis

What Is A Period?

To have a first approach to the concept of period, we will resort to the words of William Caplin:

The period […] has at its basis the idea that a musical unit of weak cadential closure is repeated so as to produce stronger cadential closure.

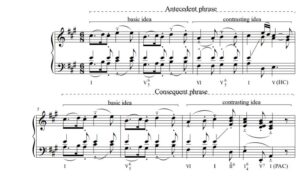

We can expand what has been explained so far with the following graph:

The Period Structure

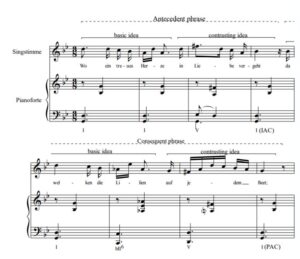

The period is an 8-m. theme built out of two phrases: a 4-m. antecedent phrase, followed by a 4-m. consequent phrase.

The antecedent phrase begins with a 2-m. basic idea, followed by a 2-m. contrasting idea. In the fourth bar we will find a weak cadence, that is, a half-cadence (HC) or, sometimes, an imperfect authentic cadence (IAC).

The consequent phrase brings a return of the original basic idea. On bars 7 and 8, we will find a contrasting idea, which may or may not resemble the one in the antecedent. The contrasting idea leads to a stronger cadence, usually a perfect authentic cadence (PAC), or more rarely, an IAC.

We could reduce the combinations of weak-strong cadences in the following way:

- If the first phrase ends with IAC, the second phrase must end with PAC.

- If the first phrase ends with HC, the second phrase must end with PAC or IAC.

In this reduction, we have not included the plagal cadence or the deceptive cadence since the composers of the classical period did not tend to use them to structure their periods.

In the graph shown below, we illustrate everything mentioned so far regarding the weak-strong relationship.

HC – PAC:

The most common weak-strong cadential relationship found in classical periods.

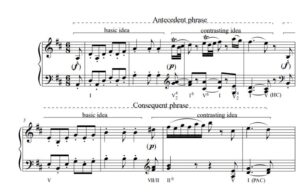

IAC – PAC:

This relationship between cadences is not so common in the classical period. However, there are many pieces where we can find it.

HC – IAC:

It is not the most common type of cadential relationship, but it is possible to find examples of this cadential relationship in classical and romantic music.

Mozart – Piano sonata No. 9 in D major, K. 311: I. Andante grazioso

Mozart – Piano sonata No. 18 in D major, K. 576: I. Allegro

Schubert – Die schöne müllerin, No. 19 “Der Müller und der Bach”

Analysis

Bars 1 and 2: These two bars present the basic idea, which is supported by the tonic harmony. Regarding the melodic contour, we can observe that the melody contains a descending 4-note stepwise motion, an ascending leap, and, finally, returns to the last note of the descending stepwise motion.

Bars 3 and 4: The contrasting idea does not present a great contrast with respect to the basic idea. It differs from the basic idea mainly by the anacrusis and the leap of the ascending third.

Bars 5 and 6: the basic idea in these bars presents a similar melodic contour to that presented in bars 1 and 2. Since the text in bars 5 and 6 contains more syllables than the text presented in bars 1 and 2, the composer is forced to make a slight rhythmic variation.

It is interesting to notice that the second time the basic idea is presented, the composer did not resort to the harmonic rhythm used in bars 1 and 2, but produced a harmonic acceleration by selecting the tonic chord for bar 5 and the Neapolitan chord for bar 6.

Bars 7 and 8: In these bars, we find the contrasting idea. We could say that this is a new melodic material, since the melody presented in bars 7 and 8 does not contain many elements in common with the contrasting idea presented in bars 3 and 4.

Unlike the Mozartian periods analysed, Schubert ends the first phrase with an imperfect authentic cadence, and ends the second phrase with a perfect authentic cadence. A relationship between cadences that, as we mentioned at the beginning of the article, is not the most frequent in the common practice period, but it is still possible to find it in numerous compositions.

Summary by Juan Rezzuto

OVERVIEW

The main features of a “period” theme are:

- Weak middle cadence

- Returning basic idea (instead of repeated)

When I mention the latter as “main features”, I mean: “these are facts that differentiate the period from the sentence”.

The period as a formal type contains only two functions/phrases:

- Antecedent

- Consequent

The Antecedent is built up of:

- 2 m. Basic idea: the same as in the sentence

- 2 m. Contrasting idea: -particular to the period- can share some characteristics with the continuation function of the sentence

The Consequent phrase brings a return of the “b.i.” followed by a new contrasting idea which might not resemble the one on the antecedent. The consequent characteristically and univocally ends on a PAC and very rarely on a IAC.

IN DETAIL…

Basic Idea

Exactly the same as in the sentence with the difference that instead of being immediately repeated, it returns at the beginning of the consequent.

Contrasting Idea

The contrast is achieved by means of melodic-motivic change. The contrasting idea might even introduce brand new motives. The supporting harmonic progressions can also be used as a mean of contrast. The contrast can be subtle or radical.

If the contrasting idea is supported in full by a cadential progression then it can be called “cadential idea”, the same as in the sentence.

Weak Cadential Closure

The partial closure – the ending of the antecedent – should always be supported by an HC, or more rarely, by an IAC -it can never be a PAC-

Cadence Categorization – Strongest to Weakest

- PAC

- IAC

- HC

Return of the b.i.

The return of the basic idea behaves in the same way the repetition of the basic idea does in the sentence (Exact repetition, statement-response or sequential).

Strong Cadential Closure

The consequent phrase most often ends in a PAC and rarely on an IAC. The cadential progression will start earlier than in the antecedent for the obvious reason that the last chord is the “I” instead of the “V”. This means, the progression needs an extra chord to conclude and therefore needs to start sooner.

Boundary Process

Lead-in

It is a brief musical idea that links antecedent and consequent in order to keep the flow. Conceptually the lead-in could be eliminated.

Elision

An elision happens when the end of one formula unit directly coincides with the beginning of the subsequent unit.

Even when the antecedent seems to elide with the consequent, this is just a superficial impression. The classical repertoire proves the later is just a misperception. The asymmetry that could arise makes this analysis unviable.

Ends and Stops

An “end” requires a cadence while a “stop” implies a discontinuation of the musical stream.

Mini Sentence

The mini sentence arises when the basic idea is built up of two 1 m. motives. The mini-sentences normally come in pairs.

Modulating Period – Cadential Strengths

In the majority of cases the period will start and end on the same key. Regardless of the keys in question, the cadences retain the syntactical strength corresponding to their types.

Differences and similarities: Period Sentence

Similarities

- Both themes are normatively eight measures in length, divided into two 4-m. phrases.

- Both themes end with a cadence

- Both themes begin with a 2 m. basic idea which is restated later in the theme

Differences

- The sentence has one cadence; the period has two cadences.

- The sentence can end with any cadence type (PAC, IAC, or HC); the period cannot end with an HC.

- In the sentence, the basic idea is repeated within the presentation phrase; in the period, the basic idea returns at the start of the consequent phrase.

- The sentence motivically pushes forward while the period reinforces a sense of stability.

We have reached the end of this article.

In the next article of this series, we will talk about how to Compose a Period (and we will include a composition of our own!).

#Haydnproject #HaydnProject #compositionlondon #composition #Caplin