Music Theory Resoucers, Uncategorized

Deceptive cadence

Function and use of the Deceptive cadence

All terms and examples are taken from W. Caplin’s Classical Form.

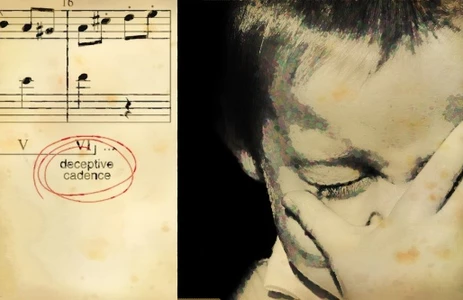

A deceptive cadence is represented by the failure to realise an implied authentic cadence by replacing the final tonic with another harmony (usually VI or I6), which nonetheless represents the end of the current cadential progression.

Definition of deceptive cadence- by William Caplin

Deceptive cadence

Cadence, deceptive cadence

Some basic notes

- Basic ideas do not end in cadences. Why? Mainly because a basic idea is harmonically static. The main variables it develops are rhythm, melody and texture.

- A deceptive cadence is a favourite device for extending form. It is found more often in the “Minuet” than in the first movement of a sonata -extended cadences are used to extend “cadential function”–

- To realise a deceptive cadence, we should find a deceptive harmonic cadence aligned with a syntax reinforcing this inconclusive resolution.

- In the absence of an adequate “non-resolving” syntax, we might end with “deceptive resolution” as opposed to a deceptive cadence.

deceptive cadence

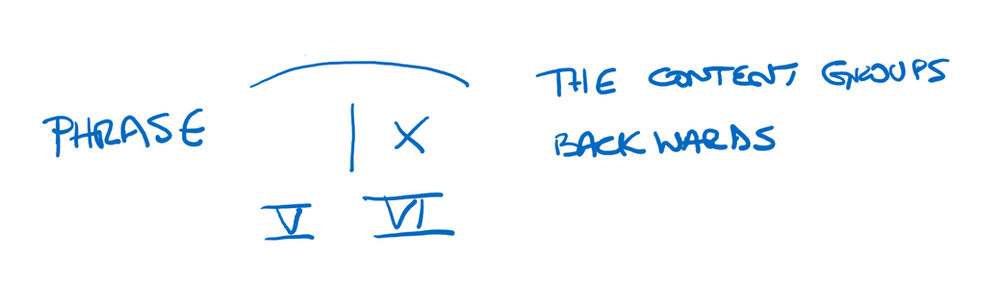

When we say the content groups backwards, we mean that the ending of the cadence makes sense coming from before the ending point.

This kind of grouping is what reinforces the sense of “deceptive cadence”. It is also important to be able to spot an HC or a PAC beyond the deceptive cadence. The latter, in conjunction with some interpolated material in between the deceptive cadence and the definite resolution, can confirm the deceptive cadence as such.

Deceptive resolution NOT deceptive cadence

In this example -p.274, e.g. 8.7 / Haydn, Piano Sonata in E, H.22, iii, 9-16-, the arrival on VI at bar 14 somehow does not produce a sense of interruption in a way in which we can confirm a deceptive cadence.

The main reason is the lack of any sort of interpolated material that can procrastinate the closure of the phrase.

On the contrary, the expected cadence begins immediately after stoping the music impulse and closing the theme.

Here -e.g.5.22 p.173 / Mozart, Trio in G, K. 496, ii, 8-12- we can also see, by the end of bar 8 and taking most of bar 9, a clear deceptive cadential harmonic progression leading to its expective deceptive -harmonic- resolution.

Due to the point in music where the deceptive resolution is used, and the purpose of its introduction, we can not consider it a deceptive cadence as well. The syntax does not reinforce the idea of “deceptive cadence” here.

It also aids in this position the fact that the PAC has already happened. Therefore, the

“deceptive resolution” does not align with the concept of “procrastinating a thematic closure” but its purpose is to embellish an already achieved closure. The latter means that a resolving instance does not follow the “deceptive resolution”, therefore there is no “deceptive cadence”.

Most common uses

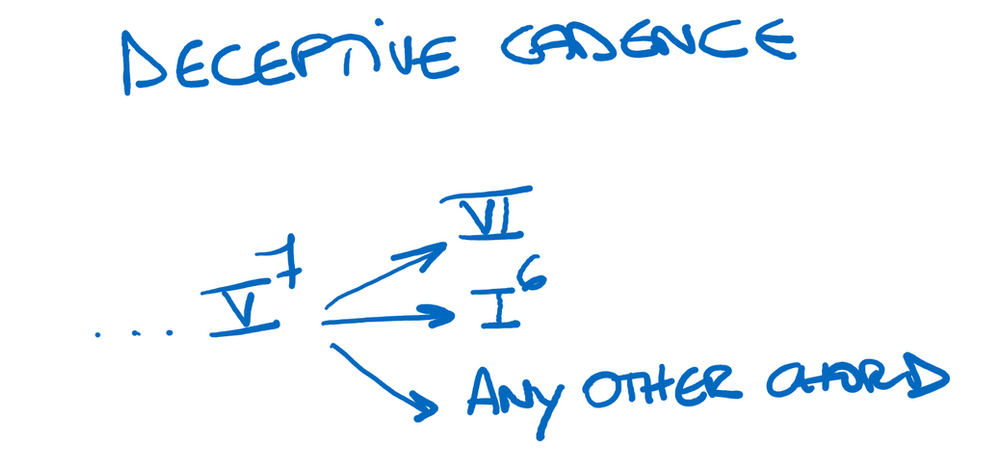

V7—> VI

In this example -p.153, e.g. 5.5 / Mozart, Piano Sonata in A minor, K. 310, iii, 9-20- the deceptive cadence motivates a repetition of the contrasting idea. The repetition of the contrasting idea aligns both the non-resolving harmonic progression with the non-resolving syntax.

In the example above -e.g. 6.10 p.204 / Mozart, Clarinet Trio in E-flat, K. 498, i, 1-16-, we can see the deceptive cadence used most conventionally. It then motivates an extension, in this case, the repetition of the “cont—>cadential” function.

In the example above -e.g.10.08 p.321 / Mozart, Symphony No. 39 in E flat, K. 543, i, 49-71-, the “deceptive cadence” on measure 65 is also used most commonly, to foster an extension. In this case, the extension comes in the shape of a repetition of the “cont.—>cadential” function which this time resolves on a PAC.

It is important that the PAC arrives after the deceptive cadence. In this case, we will most probably be sure we are in front of a deceptive cadence as opposed to a deceptive resolution.

In this rather complex example -e.g.12.5 p.388 / Mozart, Piano Sonata in C minor, K. 457, i, 42-53- we can see another traditional use of the deceptive cadence. This time motivating the repetition of the very short continuation on bars 44 and 45. As expected this repetition leads into a cadential function showcasing an ECP ending in a PAC on bar 59.

In this particular case -e.g. 15.7 p.558 / Haydn, Piano Trio in C, iii, 245-250-, we could ask why this succession of deceptive cadences are not considered deceptive resolutions? The answer is that the requirement of having the PAC coming afterwards is complied with in bar 249.

The deceptive cadence provides a temporary goal, therefore still “more needs to happen”. That “more” that needs to happen is normally the PAC.

In this example -p. 527 e.g.14.14 / Haydn, Piano Sonata in C, H. 21, ii, 40-48- we find a deceptive cadence used to kick in a transition. The transition comes in the shape of a repeated cadential function of the main theme, but it actually presents or anticipates the material of the subordinate theme.

In this example -p. 633 e.g. 18.1 / Haydn, String Quartet in G, NO. 1, iii, 33-40- the deceptive cadence is used to extend the theme using a sequence.

In this example -p.626 -book pagination- e.g.18.11 / Beethoven, Piano Sonata in E-flat, Op. 7, iii, an excerpt from bar 79-95- we can see how the succeeded dec. cad. help to extend the ECP. Remaining always at pre-cadential position helps the framing and the concept of “procrastinated resolution”.

V7—> Another chord

Beethoven, Piano Sonata in E-fl at, Op. 7, ii, 1–24

In this example, the introduction of the VII of the II in its diminished 7th version allows a second continuation to arise. This second continuation allows Beethoven to revisit a motive from the beginning of the theme; this time he applies “fortissimi” while he increments the melodic density.

Conclusion

In order to safely label a passage as ending on a “deceptive cadence” we should see:

- A segment of music starting from the deceptive cadence onwards which opens a new function or contains different material to the cadence itself.

- The introduction of the latter mentioned material produces the deceptive cadence to group backwards and not with the material introduced after it.

- The arrival to a “resolving” cadence should always and actually happen after the deceptive cadence.

For further clarification, you can check our three streamed masterclasses on the topic of Deceptive Cadence.

https://youtu.be/jaAcz0X3qO0https://youtu.be/cITLuqnuKS8https://youtu.be/xmZmfVeC974

All examples are taken from William Caplin’s – Classical Form – Oxford University Press

In order to see the examples, we strongly recommend the purchase of the book http://www.music.mcgill.ca/~caplin/analyzing-classical-form.html

Do not forget to expand your knowledge on cadences. Follow now my series for WKMT:

#compositionlessons #cadence #deceptive #cadencemeaning #definecadence #deceptivecadence